Maurice Colclough

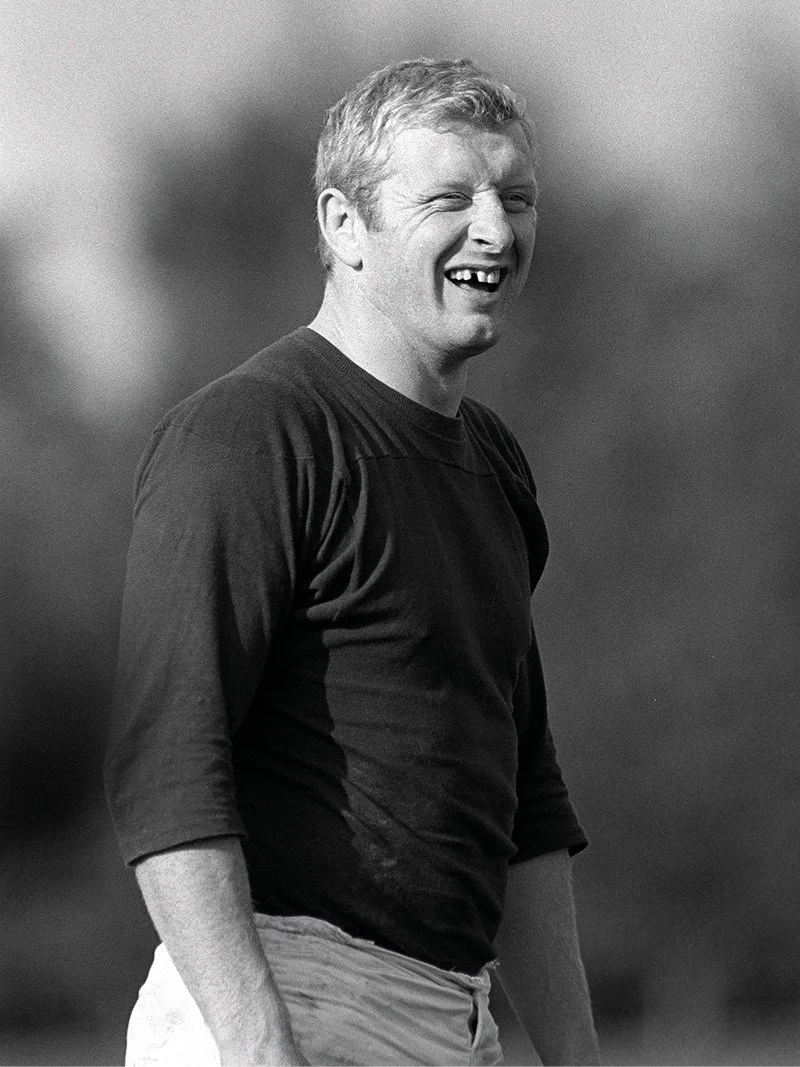

On a 1970s Penguins tour of the Soviet Union, a destination too risky for England, where hotel rooms were bugged and receptions frosty, one man made a swift trade selling jeans to KGB agents. Maurice Colclough was unique, as memorable off the pitch, as he was on it.

Mention the name of Maurice Colclough to those who played alongside him and you’ll probably get one of two responses.

First, there is Maurice the player. They will speak of him in glowing terms, as one of England’s finest, blessed with a combination of strength, height and speed.

He was also one of the first Englishmen to play club rugby in France and remains a cult figure in the town of Angoulême where he suddenly turned up as a wide-eyed nineteen-year-old and left as a rugby legend.

Then there is Maurice the team-mate. They will talk about the pranks, the team talks inspired by Shakespeare’s Henry V, and the entrepreneur. Indeed, he was once described as ‘the Arthur Daley of rugby’ by former England captain Roger Uttley, likening Maurice to TV’s fictional wheeler-dealer.

There was also Maurice the man, the husband and father. In his final years, he embraced Christianity and wanted to turn a boat he owned into a floating Christian ministry to help young people. This happened after he’d been diagnosed with a brain tumour that would see his life cut short in 2006 aged just 52.

Whichever version you gravitate towards, Maurice Colclough stands out as one of the more remarkable figures in rugby.

Born on 2 September, 1953, his father was an army officer while his mother often struggled to cope with Maurice’s seemingly boundless energy and so he was packed off to boarding school aged nine. Then, aged eleven, he was enrolled at the Duke of York’s Royal Military School in Dover which was also his dad’s alma mater.

It was at Duke of York’s that Maurice first learned to play rugby and he went on to play for the Kent Schools team. During his school holidays, he would see his mother in Selsey Bill at the southernmost part of West Sussex. His parents had split up and his mum was living on a caravan site. It was in Selsey Bill that Maurice had his first dinghy – and sailing would play a big part in his life.

He went to Liverpool University to study geology, but spent too much time enjoying the social side of university life, then switched to Egyptology, but ultimately dropped out. Yet his time in Liverpool was far from wasted. He played for Liverpool St Helens RFC, where he first came up against Bill Beaumont who would later become his captain in England’s 1980 Grand Slam-winning team.

“Fylde played them twice a season once in October and then around Christmas/New Year,” Bill recalls. “I remember playing against him at Fylde, seeing this huge guy with massive frizzy ginger hair and he had obviously been out the night before! And I had a decent game that day, but we then went back to play them in the return game, and he absolutely murdered me.”

Maurice left Liverpool and decided to go travelling around France. While working his way around the country, he was kicked off a train for apparently having the wrong ticket and hitched a lift – a life-changing car journey.

The driver just happened to be the coach of Angoulême, based in the south-west of France, and Maurice clearly made a good first impression. Following his first match he was given a flat, a car and expenses to cover the cost of his trip from England. They also set him up with a job, first as a welder, before he ended up running a bar.

Rumour and suspicion surrounded how Angoulême were funded. This was fuelled by the fact the town’s mayor was Jean-Michel Boucheron, a politician who lived by the Cs – charismatic, colourful, and corrupt.

Maurice spent several years there and thrived in French club rugby. He became known as the ‘Prince of Angoulême’, and you can still see pictures of him gracing walls of bars and restaurants in the town.

penguinrugby.com

Naturally, he embraced the local culture and went into a partnership with a friend from Liverpool University. Together, they bought boats from the Norfolk Broads and set up a company called Holiday Charante, running riverboat cruises on the Charante River. He then recruited other friends to help build a house and office alongside the river and his mum would take the bookings.

Before he’d left for France, Maurice had already made his mark on English rugby, with his performances for Liverpool, together with County Championship games for Sussex and Lancashire.

Invitational rugby followed at Angoulême, where, in 1977, he was selected to join Penguin Rugby who had been invited by Russia to take part in the Eastern European Inter-Nations Championship (EEINC) after England had declined.

In the 1970s, Penguin Rugby, the self-proclaimed ‘World’s Premier Rugby Touring Side’, attracted players who had either been overlooked by the international selectors or hadn’t sustained their breakthrough into the highest levels of the game. It was an opportunity for them to get a second, or even third chance of showing their ability against international opposition.

Among them was Derek Wyatt, who would go on to play for England and the Barbarians and would become founder of the Women’s Sports Foundation and serve as MP for Sittingbourne and Sheppey. “England had been approached to play but can you imagine people at the RFU who were to the right of the Tory party allowing a team to go to Russia!” explains Derek, who was a member of the Penguin squad that played in the EEINC.

The tournament was an opportunity for emerging talent to show if they could cut it against more experienced players. “One of the reasons why it was so popular with the players was everybody knew that the selectors would come and watch us although the only thing was that we never played in England,” says Derek.

Also, on that tour to Russia, or the Soviet Union as it was back then, was Philip Keith-Roach who would become scrum coach for England’s World Cup winning team in 2003, and Ollie Campbell, who had earned one cap for Ireland in 1976 before being dropped but would later go on to become one of Ireland’s greatest fly-halfs and a veteran of two Lions tours.

Then there was Maurice. Nobody knew much about him before the tour, but he ended up making his own special contribution to the history of Penguin Rugby both on and off the pitch. Derek takes up the story. “We flew out on an Aeroflot plane [an airline which was notorious for its safety record] to Moscow and then trained in Gorky Park. It was like eighty degrees out there and we jumped into the Moskva to cool down and came out covered in shit. It was quite an eye-opener.

“Russia was fascinating. All our hotel rooms were bugged. You had to shout into the microphones to say, ‘We’re home now!’.

“Maurice,” continues Derek, “to his great credit, brought jeans and t-shirts and sold them from underneath a table in our hotel in Moscow for hundreds of pounds. He was selling to the KGB, they couldn’t wait to get their hands on Levi’s!

“The rugby was terrific. We all thought Maurice was fantastic as well. He was a giant at 6ft 4in but also so quick. There wasn’t any fat on him. He loved training but was mentally strong and if you don’t have that bit, you won’t be a good player.”

Maurice caught the attention of England’s selectors and made his international debut a few months later in 1978 against Scotland where he was reunited with Bill and they would go on to form a formidable pairing in the second row. “He used to call me the ‘Chief School Prefect’,” says Bill, “whereas he wanted to challenge authority, but in a good way.”

Although he didn’t figure at all in England’s 1979 Five Nations squad, he continued to play club rugby in France and his form and performances for Angoulême eventually saw him recalled into the England set up for the 1980 Five Nations campaign. He missed the first match against Ireland because of injury and Nigel Horton proved to be a more than able deputy, but Horton was still unceremoniously dropped for the next game away to France as by then Maurice was viewed as an automatic first-choice player. “I thought it would be a case of normal English selectors, and they would have kept the same team,” says Bill. “But they told Nigel on Saturday night, straight after the game, that he wasn’t going to be picked. And he played bloody well against Ireland.”

To prove his fitness, Maurice played for Angoulême the day after that victory in Ireland and then flew to Coventry for a training session with England.

He then became a secret weapon for England for the second match of that 1980 campaign, against France in Paris, which they won 17-3 to claim their first victory at the Parc des Princes. As Bill recalls, unbeknown to the French, Maurice had figured out all their lineout signals, to help deliver a victory that was a pivotal moment in England’s 1980 Grand Slam.

The final match of that campaign saw England beat Scotland 30-18 at Murrayfield. There was one moment early in the match when Bill and Maurice combined to lay down a marker on the opposition. It was described by England hooker Peter Wheeler as “the best scrum I’ve ever been part of” adding that “It took place near Scotland’s line and Billy called for a double shove. I can still recall the feeling as we surged forward, like a supercharged car in overdrive. It was an uncommon experience. Occasionally it happened at the end of a club game, but you don’t expect that surge in the early stages of an international.”

Two years later, Paris was also the scene of an infamous incident that one could argue has a tendency to overshadow what Maurice achieved as a player for England whenever stories are told about him. After a 1982 25-17 England victory over France, both teams gathered for an after-match dinner. There are various accounts of what happened next although they all have the same ending.

Jeff Probyn’s version is that dinner had been a soporific occasion, so Maurice decided to liven it up by engaging in a drinking game with team-mate Colin Smart.

It started with Maurice downing a half, followed by a pint of beer, followed by a half bottle of red wine, followed by a bottle of red, followed by a bottle of aftershave (which had been a gift left for all the players on their dinner tables) . What Colin didn’t see was that Maurice had emptied the aftershave bottle, filled it with water, and then proceeded to down the contents. So, Colin followed suit and then had to be rushed to the nearest hospital so he could get his stomach pumped. England scrum-half Steve Smith later said, “He may have been unwell, but Colin had the nicest breath I’ve smelt.”

That was far from the only incident abroad. One time in Dublin Maurice dived naked into the Liffey. The Gardai were waiting for him when he came out of the river and he had to pay a fine in court.

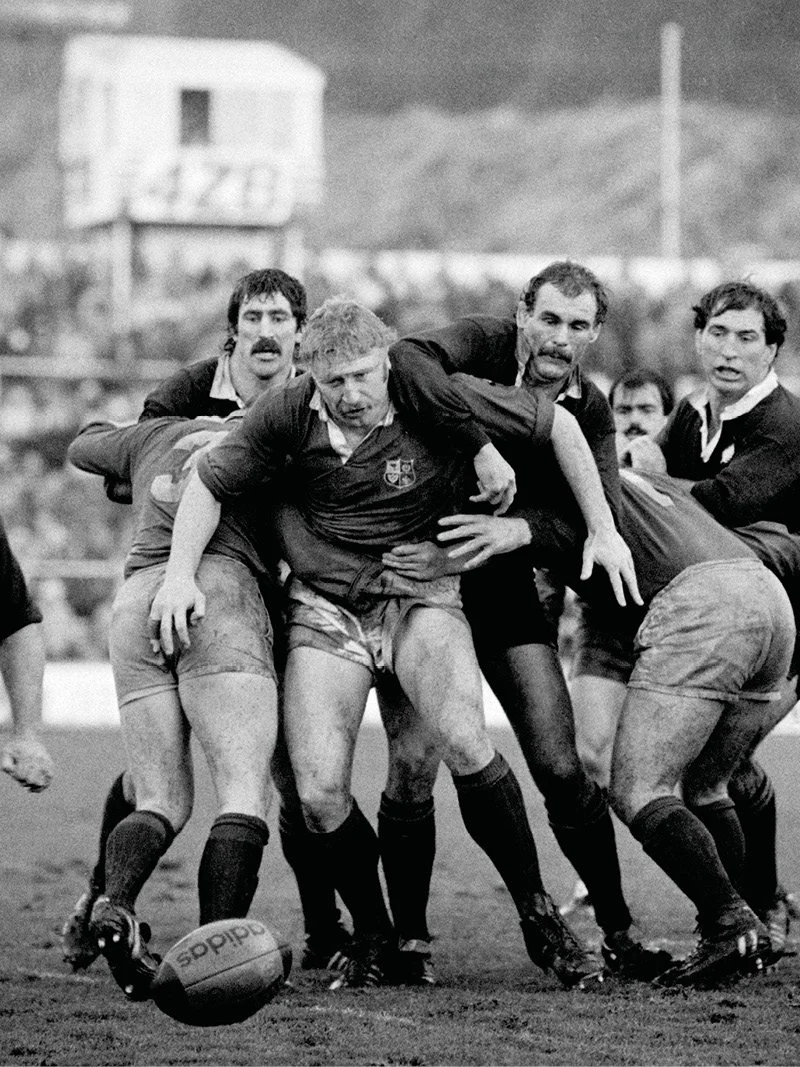

Maurice and Bill also played alongside each other on the Lions tour of South Africa in 1980, a trip notable as much for hard-drinking and devil-may-care attitude of certain players including Maurice, as the rugby. On one occasion tour manager Syd Millar was speaking at a dinner and Maurice poured a tub of beans over his head. It was a rugby tour of the times.

Perhaps not surprisingly, he put in his best Five Nations performances against the French although Bill picks out a 15-11 victory over Australia in January 1982 as the standout. “He was just unbelievably good that day. He was a great athlete. You know, he probably wasn’t the most coordinated player I’d ever come across. But when he set his mind to it…”

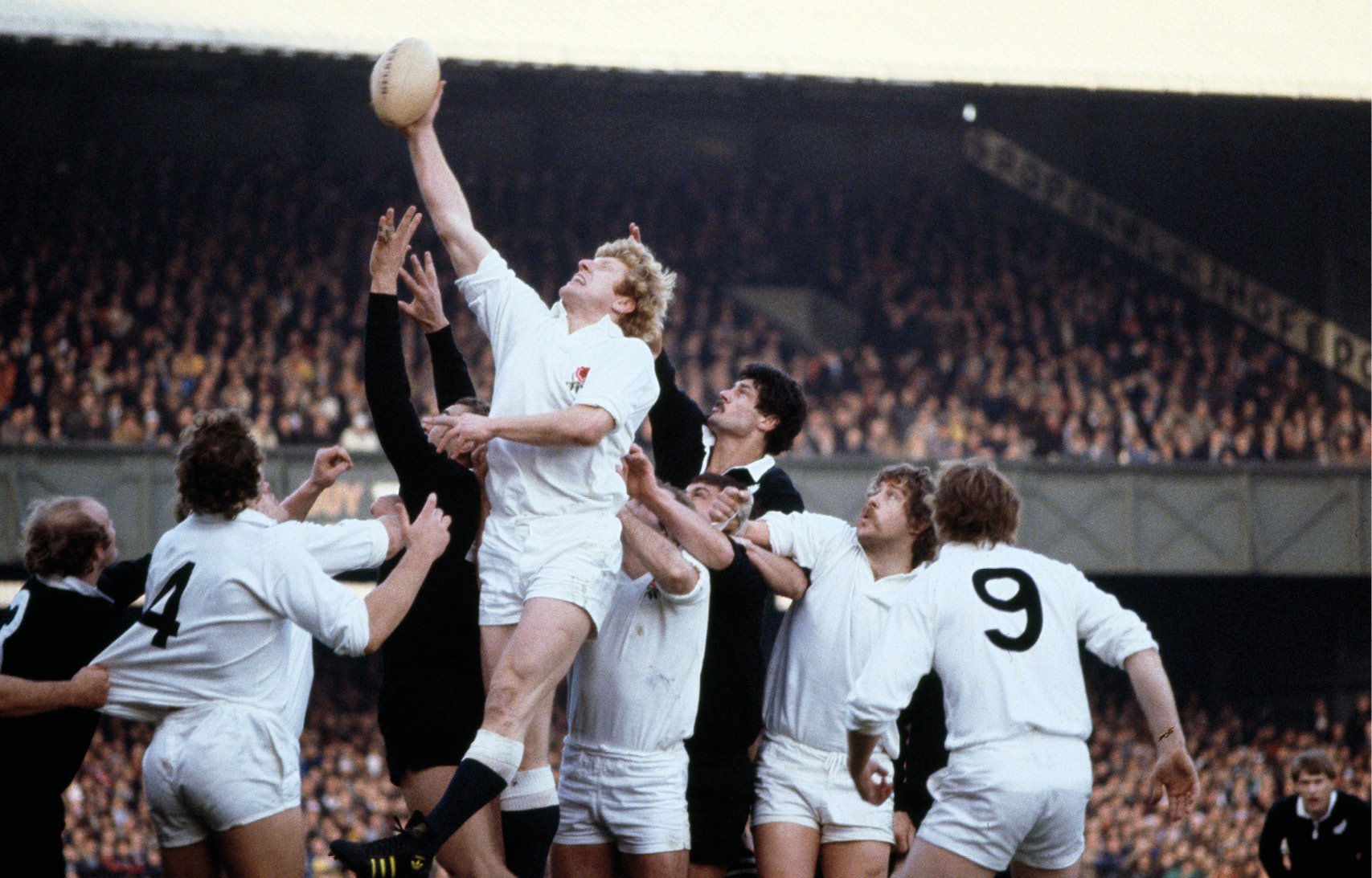

Another stellar match for England came in 1983 when they beat New Zealand 15-9 at Twickenham. Maurice and Peter Wheeler were the only survivors from that 1980 Grand Slam winning team and it was Maurice who scored the winning try, powering his way over the line from a lineout.

Peter then hailed him as ‘the Marquis de Colclough’ as a nod to Prince Obolensky, the Russian who scored two tries in 1936 and had played a key role in England’s only other victory over New Zealand at Twickenham at that point.

At club level, Maurice would go on to join Wasps from Angoulême where he became captain. According to one player, “He modelled himself on Henry V’s speech before Agincourt, but Maurice’s words contained more spittle and invective than imagery. He finished once with a tumultuous battle cry, then turned to lead us out onto the pitch and fell over on the highly polished floor.”

That same year, 1983, Maurice met his future wife Annie at an event to publicise the new Cardiff Arms Park. Three years later they were married and Maurice moved to Swansea RFC from Wasps. Again, he was juggling rugby with his entrepreneurial pursuits; he’d bought a small dockyard and converted a trawler into a Spanish galleon, getting the boat towed up to Swansea Marina to become a floating pub and restaurant.

Maurice should’ve played in the inaugural Rugby World Cup in 1987, but those hopes were scuppered due to a serious bout of mumps and it led to his retirement from international rugby in the same year with 25 England caps and seven appearances for the Lions to his name.

Life after rugby often proves to be complicated and Maurice was no different, but his particular addiction was business. Instead of focusing on one or two ventures, he always wanted to have fingers in many pies and irons in multiple fires. Sometimes that business acumen wasn’t as strong as his work ethic.

In 1995, the Colcloughs bought a boat, named it the Four Sisters and headed off on their travels eventually settling in South Africa where Maurice became managing director of a company involved in slot machines. Annie and the daughters came back to Wales after the family were victims of a car-jacking. Maurice would visit his family during the school holidays and three of the daughters ended up playing rugby at Llandovery College. The eldest, Morgane, recalled that when they were little girls, “all three of us would be hanging on to Dad’s legs as he ran with the ball”.

However, Dad’s influence didn’t go as far as their allegiances – whenever the family watched England v Wales, everyone else supported the Welsh.

Annie and the daughters were also practising Christians whereas Maurice did not embrace religion, until 2003 when their lives would be turned upside down.

It was on a visit to see Maurice in South Africa, that Annie couldn’t help but see that when he smiled only half of his mouth moved. She took him to hospital and he was diagnosed with a brain tumour. The doctors said it was malignant and gave him a year to live. They operated on him and soon after that, Maurice became a Christian. It was at this time that a sailing trainer by the name of Chris Wren received the following correspondence from a friend:

‘I recently had an email conversation with a chap called Martin Bateman at Operation Mobilisation (a Christian missionary organisation) who knows a 70s/80s rugby star who is unfortunately ill with a brain tumour.

This chap’s name is Maurice Colclough and he has a boat in South Africa which he wants to launch into the Lord’s work.’

Martin then followed up by explaining that Maurice was one of his heroes, and that he wanted “to start a yachting ministry” using the boat, which was berthed in Cape Town. Chris offered to bring the boat from Agadir to Milford Haven, but the journey was fraught with complications. He discovered the boat – anything but ship-shape – wasn’t insured, there was a standoff with a gunboat, and one of the crew members almost died. A three-week journey ended up taking three months. This totally haphazard trip seemed entirely fitting given the vessel’s owner.

Even if that boat could have been restored to realise Maurice’s ambition of becoming a floating ministry, it is doubtful he would have lived to have seen it happen as the tumour had grown back in the same cavity. “He rang me and said he was in South Africa and that he was coming back to Wales,” says Bill Beaumont. “He asked me if I knew anybody in Wales who could look at the tumour. So, I rang up a pal of mine at the Welsh Rugby Union, I think it was Gerald Davies. I said, ‘Can you put me in touch with anybody?’.

“He said ‘Yeah, one of our committee doctors is the top oncology guy at the Whitchurch Hospital in Cardiff.’ So, I went to visit Maurice several times in Cardiff. Against the odds, he lived for another three years.”

Maurice passed away on 27 January, 2006. In Angouleme, they staged a testimonial game in his honour and one of his daughters started the match with a drop kick.

The last time Bill and Maurice met was at Twickenham in 2005. “He gave me a bottle of brandy,” explains Bill, “and said, ‘drink this when we meet again’. I knew what he meant.

“When I went to his funeral a lot of the England lads were there. I brought that bottle of brandy along with me and put it on the bar. I said, ‘right guys, I said I would only drink this when we meet again. Well, here we are, Maurice’.”

Story by Ryan Herman

Pictures by Getty Images

This extract was taken from issue 29 of Rugby.

To order the print journal, click here.