John Bentley

A journey that truly began when he decided to start ‘kicking shit out of public schoolboys’, ended as cult hero of the British & Irish Lions. Scorer of a famous Lions try, a Test starter in a South Africa series victory, a dual-code rugby professional, and the most famous cameraman of the late-1990s. This is John Bentley.

Getty Images

“So”, asks British & Irish Lion number 676, “what’s two plus two?” Four. “Four plus four?” Eight. “Eight plus eight?” Sixteen. “Sixteen plus sixteen?” Thirty-two. “Thirty-two plus thirty-two?” Sixty-four. “Sixty-four plus sixty-four?” One hundred-twenty-eight. “Now, think of a vegetable, don’t tell me though.” Done.

“Carrot, right? It’s always carrot.”

It was carrot. Some British & Irish Lions tours are defined by individuals, for what happened on the pitch, or even off it, in defeat or victory. A dropped pass to lose the series, a searing run in the winning Test, incredible defence in the face of adversity, a barnstorming speech to rally the pride, or maybe even just coming up with a call that meant ‘one in, all in’. In 1997, when the British & Irish Lions embarked on a thirteen-game, six-week tour in the home of the world champions South Africa, the name that many of us of a certain generation recall is John Bentley, and it was for almost all of the reasons above. Jeremy Guscott too, perhaps, for his drop-goal to win the second Test 18-15 at King’s Park, Durban, to clinch the series and make history. But really, for that try, for that confrontation, and perhaps most important of all, that video, it has to be Bentos.

An entertainer in every sense, Bentos fills every moment; when one story finishes, his mind is already preparing another, maybe not even a story, just something to entertain, like the carrot teaser.

Sat in a leather chair with a pillow embroidered with the words, ‘Yorkshire Lad’ writ large, Bentos reels off his story, continually adding virtual ‘Post-it’ notes onto each anecdote when he remembers another connected story, but not wanting to lose the chronological thread of his own life. “We’ll come back to that one later,” he says, more than a few times.

He is now living in Brighouse, a town sandwiched between two places that mean so much to him: Cleckheaton, where he grew up and first learnt to play rugby union, and even finished his career, aged 45; and Halifax, where he had his most enjoyable spell in club rugby, albeit in the other code, rugby league. He’s 58 now, almost 59, and it’s his favourite time of the decade, a Lions year. “Once every four years, the Lions talk comes around,” he says. “And I get the opportunity to travel all over. I’m actually going out to Australia as well, so I’m looking forward to that.”

Even for the three years when there isn’t a Lions tour, his role with the tourists almost thirty years ago, still helps keep him busy. “I got employed by Leeds in 2001 when they got promoted to the Premiership, my role was to try and encourage the rugby union playing community to embrace Headingley as an opportunity to watch professional rugby union, even though it was synonymous with cricket

and rugby league.

“I got a foot in the door there because I played with the Lions,” he adds.

Rugby began early for Bentos. “I started Cleckheaton as a six-year-old playing mini rugby, so my weekend involved playing football for school on a Saturday morning, rugby league for Dewsbury on a Saturday afternoon and Sunday morning playing rugby union with Cleckheaton.

“My sports teacher drove me to Bradford Grammar School, to a Yorkshire schools trial. Now, I could play, but I was quite small as a sixteen year old, so I didn’t get picked.

“I came home and mum was making the tea in the kitchen, and she said, ‘How did you get on?’ I burst out crying, saying, ‘I didn’t get picked’. And my mum put her arm around me, and she said, ‘you can play’. I said it wasn’t that I didn’t get picked, it’s the fact that I felt inferior. I felt like a second-class citizen. My mum just put her arms around me and said, ‘Do you know, John, you can play. Just remember, when you’re on a sports field, on the rugby field, you’re as good as the boy you stand alongside. No better, no worse’.

“And I went on a bit of a crusade then, and I went kicking shit out of all the public school boys I ever played against, which was probably not their fault, but I decided that was going to be my journey to play.”

Playing both codes until he was seventeen, despite the potential riches of a career in league, he chose the then amateur union. “I wanted to play for England,” he says, simply. “That was my goal. When I was eighteen-year-old, I went to Otley for two years, and then Sale under Fran Cotton and Steve Smith.

“But throughout my rugby union career, every time I came off the field, there was always a [league] scout there saying, ‘do you want to earn this, do you want to earn that much?’. And of course rugby league scouts weren’t allowed in rugby union clubs, it was taboo to be involved with league clubs.

“But I ended up playing for England and it was supposedly one of the biggest days of my life, but it was such an anti-climax.”

He’s jumped ahead, his mind racing to the next thought, almost before he’s finished vocalising the last one. He’s skipping how he won the Country Championship with Yorkshire, then played for the North to get on the radar of England. There’s also the story of the time he was with England B, who played before the first team, in France. “We’d climbed over the fence [for the main game], we’d no tickets. I ended up having probably a little bit too much to drink, and I’m in a quartet with Paul Rendell, Judge, sadly lost now, Peter Winterbottom and Wade Dooley. “I thought I’d have a connection with Wade because I was a police officer, he was also a serving police officer, but I also sensed he didn’t particularly respect me. He didn’t particularly like me, I knew that, I could tell.

“And we ended up, a few drinks in, throwing drinks on each other. Well, it came to the last drink, and he said, ‘if you throw that on me, I’ll knock you out’. And I went to throw it and Pete Winterbottom got hold of my arm and split it all up.

“He’s huge as well. Why would you get involved in a fracas with him?”

“Anyway, they tried to split us up, but Wade put his arm around me and said, ‘no, you’re coming for a drink with me’, and I went for a drink, and I poured my heart out to him, got quite emotional about it, about a lack of respect. From that day forward, he became my minder.”

The full England cap that followed, in 1988, was against Ireland. “It’d been a day that I’d planned for and worked towards for realistically, three or four years. I always remember very nervously getting to the ground, I hadn’t slept two or three nights prior, pull me England shirt off the peg, and there was the big, juicy red rose, and I kissed it, and I went out and warmed up, and then put the shirt on, looked in the mirror and went out on the field.

“We sang the national anthem, and I cried, you know, just the emotion. Then I heard a whistle, and it had started. It was fast, it was furious, and then I heard another whistle, and it’d finished, and I’d been on the pitch for eighty minutes playing for my country, England, and I’d done nothing. I hadn’t done anything. I’d been a passenger.”

Then, there was the tour to Australia in the same year, where he earned his second cap. “I was probably remembered, for the first time, for the things that I did off the field, rather than on it, if I’m honest. I was only a young boy, 21 years old, and a little bit wild at times, and certainly had a great tour.

“I always remember Geoff Cook coming back and saying, you know, ‘[your] rugby was disappointing, but what a tourist’. Just being a prankster, I’ve always been where there’s a little bit of mischief to be had. I’ve never been far away from it, and I’m a big believer in life, even in moments of adversity, if we can smile, we’re going to be okay. And I like to make people smile. I’ve always enjoyed that.”

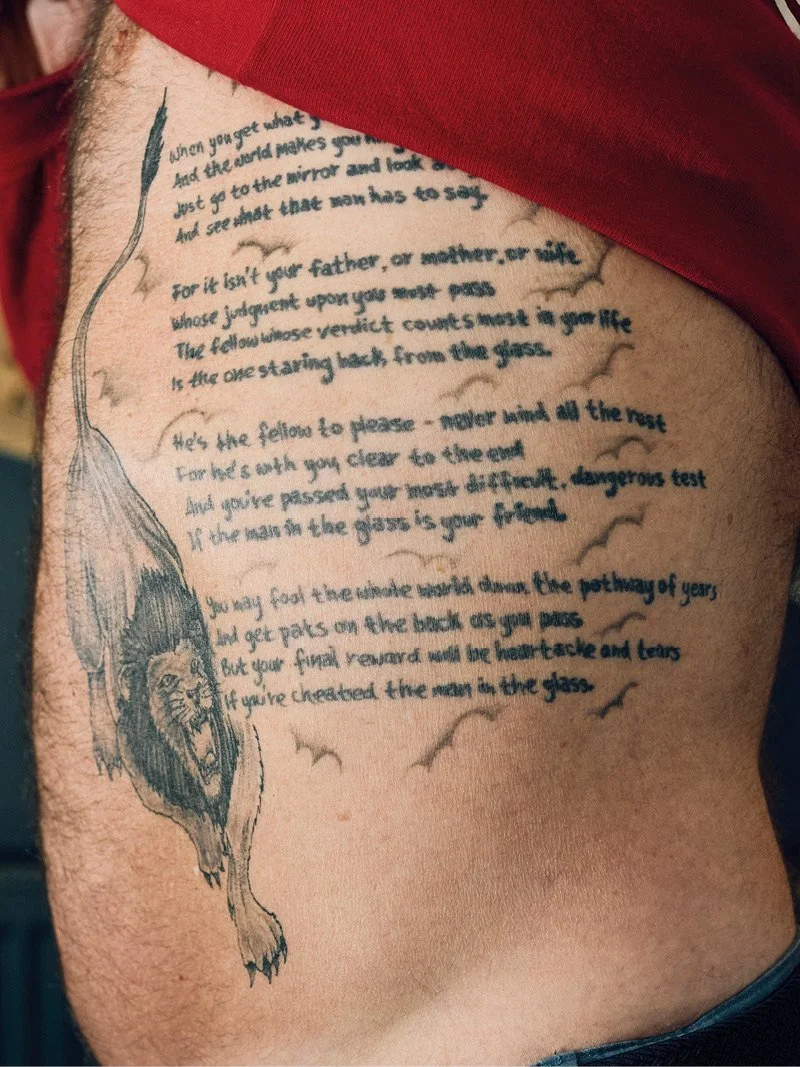

Bentos is also surprisingly earnest, continually talking about looking at the man in the mirror, and also admitting that the chip on his shoulder from that grammar school trial was often present, long after it should’ve disappeared altogether.

Although a scrum-half when he started out, he was a centre when he was contending for caps. His rival couldn’t have been more different: Will Carling. “My goal was all to do with Will Carling, and he was being earmarked to become England captain,” he explains. “They [England] had assured everybody, the players in that season, 1988/89, that getting picked for England was all going to be based on performance. And when one squad was announced, I’d played against Will Carling the day before.

“My role for Yorkshire was to destroy Will Carling [who was playing for Durham in the County Championship],” he admits.

So determined was Bentos to get one over his rival, when an injury meant he was asked to play on the wing, he refused. “In those days, playing on the wing was very different than it is now, you know; I remember growing up at school, you know, the kid on the wing was a kid who could run fast, couldn’t catch the ball, was there to make the numbers up.”

It wasn’t just Bentos who believed the England-captain-elect could have his feathers ruffled. “And of course, there was all the chat prior to the game. Will Carling was in the toilets and asked Richard Holmes, ‘where’s Bentos playing today?’. And Holmes said, ‘he’s playing in the centres and he’s going to kick shit out of you’. And I did for eighty minutes. The following day when they announced the side, Geoff Cook paused when he got to twelve in his team. He stopped and went, ‘this is probably one of the hardest decisions: Will Carling, 12’.

“And I walked out.”

Not seeing a way through, Bentos left for rugby league. “I thought this is the time now. I’d been approached on a regular basis, and was about to get married as well, so I said, ‘right, I’m going to sign’.”

He went to Leeds, with a presumption that he’d “never, ever get to play rugby union again”, although in league, he also found plenty of challenges. “I had some big problems. Number one, everybody hated Leeds. They were deemed to be the rich boys, you know, the flamboyant club. Number two, I was from rugby union, so everybody I played against thought I was soft, yeah. That never happened twice. You know, you end up getting some credibility, some respect.

“Thirdly, I was a serving police officer, so imagine playing at the likes of Featherstone and Wakefield and Castleford, who were extremely militant during the miners’ strike. Yeah, that was a little bit of a challenge, but it worked for me.”

Four years later, he went to Halifax. “Dare I say, I became a bigger fish in a smaller pond at Halifax. And Halifax for me, was a club that belonged to the people, playing at Thrum Hall, which was ten foot higher on one touch line than the other. Loved it. I had probably the happiest period in my playing career there, in terms of club rugby.”

Being paid to play rugby changed perspectives. “At Leeds, match-day winning money was £300, but if you lost it was £40, so you didn’t actually want to play on a Sunday afternoon and be the player that lost the game. And I’ve been that player, when I made a mistake at Warrington and kicked the ball out on the full, and as a result, we lost the game.

“Playing for money was very different,” he continues. “And some players were playing for money. They were doing hard, hard jobs, manual work. And actually, the difference between winning and losing on our Sunday afternoon was that, if the washing machine is broken down, and you win, you get a new washing machine. If you lose, you don’t get that.”

When union turned professional, more doors opened for Bentos, not that it was a case of one door closing, another opening. He kept both open, because the top level of league switched to a summer season, with the founding of the Super League in 1996 , which meant he could play all year round, in both codes.

“I ended up playing twelve months of the year. I signed with Newcastle, who were in the second division, Sir John Hall was funding them, we had Rob Andrew, Dean Ryan, Steve Bates…

“I basically had five years back-to-back without a break.

“It was a bit of a combination: maximising my potential,” he says of his rationale, “in terms of, I’m there as a guy with three young children, I’ve got to provide for my family and I was sought after as well.”

In a Newcastle side that was flush with internationals, despite being in the second tier, Bentos ran amok, scoring four hat-tricks in one campaign. “I got a phone call from Fran Cotton in January of 97, ‘Bentos, it’s Fran…’ ‘Yeah, I know’. I hadn’t spoken to or seen him for eight, nine years.

“He said, ‘are you available to tour with the Lions in the summer?’. And I lied, said I was, but I wasn’t, I was contracted to play rugby league in the summer. He came back, ‘Well, with all due respect, you’re running riot, second division, great team. We need to get you a run with England B. Leave it with me.’

“And he rang me back three weeks later, saying ‘Bentos, the news I’m going to share with you comes as little surprise to either of us, England won’t touch you, because of league.’ Whereas, the Welsh boys came straight into the Wales team.”

Cotton left him with the fact they were watching, and it was down to him. “I was in the right place at the right time, fortunately for me, with the right type of people picking what they felt was the right type of player to go to South Africa.”

The prospective Lions first met in Birmingham. “There were 62 professional rugby players, six of us rugby league, which was unheard of,” recalls Bentos. “Previously, you weren’t allowed in the same room as your counterparts but Fran Cotton spoke about the challenge ahead.

“We were given sight of a contract,” he explains. “It was £10,000 for being picked for the Lions, taking part in the tour and completing it paid pro rata. So if you’re injured halfway through, you only got £5,000. Bonuses: £1,500 for winning one Test match, £5,000 for winning the Test series and, because there had been problems on the previous tour, £2,000 for behaving.

“There was no chance I was getting that,” he quickly adds.

The series bonus as well, says Bentley, was also highly unlikely to get paid out.

While selection was far from guaranteed, his wife, Sandy, still had doubts, as a Lions tour would bring in only a quarter of what the same time in league would bring, plus the risk of injury against such volatile opposition was certainly a considerable risk. “I was 30 years old as well. Everything was right in my world, as a player, in my life, you know my family, which has been extremely important to me throughout my life, a big focus, everything was just right.”

When the selection letter arrived, or rather Bentos read his name on teletext – as the post in his area didn’t arrive until later in the day – Sandy stood firm. “She told me I couldn’t go,” he says. “I sat on it for two days, and sat her down after two days and said, ‘you know, there’s some things in life far more important than money. You have to let me go, because I’ll spend the rest of my life thinking, what if?’ and she said, ‘right, you go’.

“And I look back and now, and, you know, I still remind her. I say, ‘you told me, 27-28 years ago, I couldn’t go on the tour, and actually, if I hadn’t, we wouldn’t be doing this, or we wouldn’t be here, or we’re in Marseille…’ And she says to me, ‘Bentley, you made one right decision, one right decision, that’s it’.”

South Africa wasn’t just the pinnacle of a career in rugby, it was also something of a homecoming. “I grew up in South Africa,” he says. “We emigrated when I was four years old, and spent three years in Cape Town. My dad’s job took us there, he was a sheet metal worker, nothing flamboyant or anything. But we emigrated out there, although my mum struggled with the apartheid so we came back. It’s a magical country though.

“We came back [to England] on a boat, and there was a doctor who was a traveling South African, and I was seven years old, and I shouted to Mum, ‘Mum there’s a kaffir in the pool’. Very horrible. My mum went across and apologised, because I didn’t know what I’d done wrong, although the doctor was fine. But people were subservient. Yeah, it was terrible. In the world that we live in, everybody’s got an opportunity. Everybody should be equal.”

He remembers very clearly when he left home to return to South Africa, this time as a Lion. “It was 11th May, 1997, and my son was seven years old, my daughters were five, and the little one, Millie, was six months.”

Travelling down with club-mate Tony Underwood – one of five Newcastle players selected – he asked about the English contingent, with one player in particular intriguing Bentos. “I’d formed an opinion of Guscott,” says Bentos, “and I thought he was soft, because he didn’t play in that game when Bath played against Wigan, and they got £10,000 a man for playing it.

“And I asked Tony, and he said, ‘Bentos, if he respects you, you’ll get on very well. He will respect you…

“I said, ‘you know what, Tony, I’ll know whether or not he does, and actually, if he doesn’t, I’ll pick him as a partner in training, and he’ll hold the shield and I’ll go straight over the top of it and into the bridge of his nose, I’ll smack him.”

For all his bravado, Bentos was going to South Africa not to be a prankster. “My wife had allowed me to go, so it wasn’t just about entertaining people, it had to be about the rugby,” he says.

When the players met, Guscott was among the first to say hello. “He said, ‘Bentos, I’ve heard a lot about you’. And we shook hands. He said, ‘I’m looking to spend some time with you’. And you know what? I’d got it so wrong with him in terms of what took place over the forthcoming ten weeks or so. He wasn’t soft.

“I asked him about why he didn’t play in the Bath and Wigan matches, he said, ‘I knew they [the two codes] were different games, why did I need to go and get me head kicked in to have that proven?’. We ended up being great mates.”

The film crew who were there to shoot a fly-on-the-wall video, the iconic Living with Lions, were on board despite reservations from the management. They soon picked out Bentos as the ideal insider and handed him a camcorder [Google it, if you’re under forty], unleashing a man who would deliver the kind of content that modern-day Lions fans have no hope of ever seeing. “It’s very real, never to be repeated,” he says. “And actually, one of the key ingredients to me having the camera was none of the players knew. After three weeks, I said, ‘Do you know what? I kept giving them tapes and what have you, and you’re only getting my perspective of the tour’. And I gave the camera to Doddie [Weir], who got injured, cruelly, got his leg snapped in half. Rob Wainwright used it a bit as well.”

It also helped that what was happening on the pitch was so good. “We were winning,” he says. “We only lost two games out of thirteen, and we were all winning, and that was a big ingredient equally as well.”

Any rules on alcohol consumption? “None,” he says. “If you want to drink, go for a drink, but just recognise, upon returning to the hotel, there is somebody in that hotel preparing for the biggest game of their life, so just keep it down.

“I became the entertainment officer,” continues Bentos, “somebody said during the team-building that we need an entertainment officer, and there’s about five players, six players, shout my name out. I said, ‘No, I’m not doing it’. And Johno said, ‘yeah, yeah, you’re doing it’. I said, ‘well, I’m not doing it on my own. He said, ‘well, pick whoever you want.’ Who’s the first person I asked? Guscott Because I knew that if I’m in charge, we’re doing this, we’re doing that – if he didn’t want to do it, he wouldn’t do it. So I got him involved. The other two would be Scott Gibbs, get the Welsh on board, and Doddie, to get the Scots.

“I had a budget, a little bit of a slush fund from Scottish Provident who were our sponsors; everywhere we go we’d put things on like clay pigeon shooting.”

Getty Images

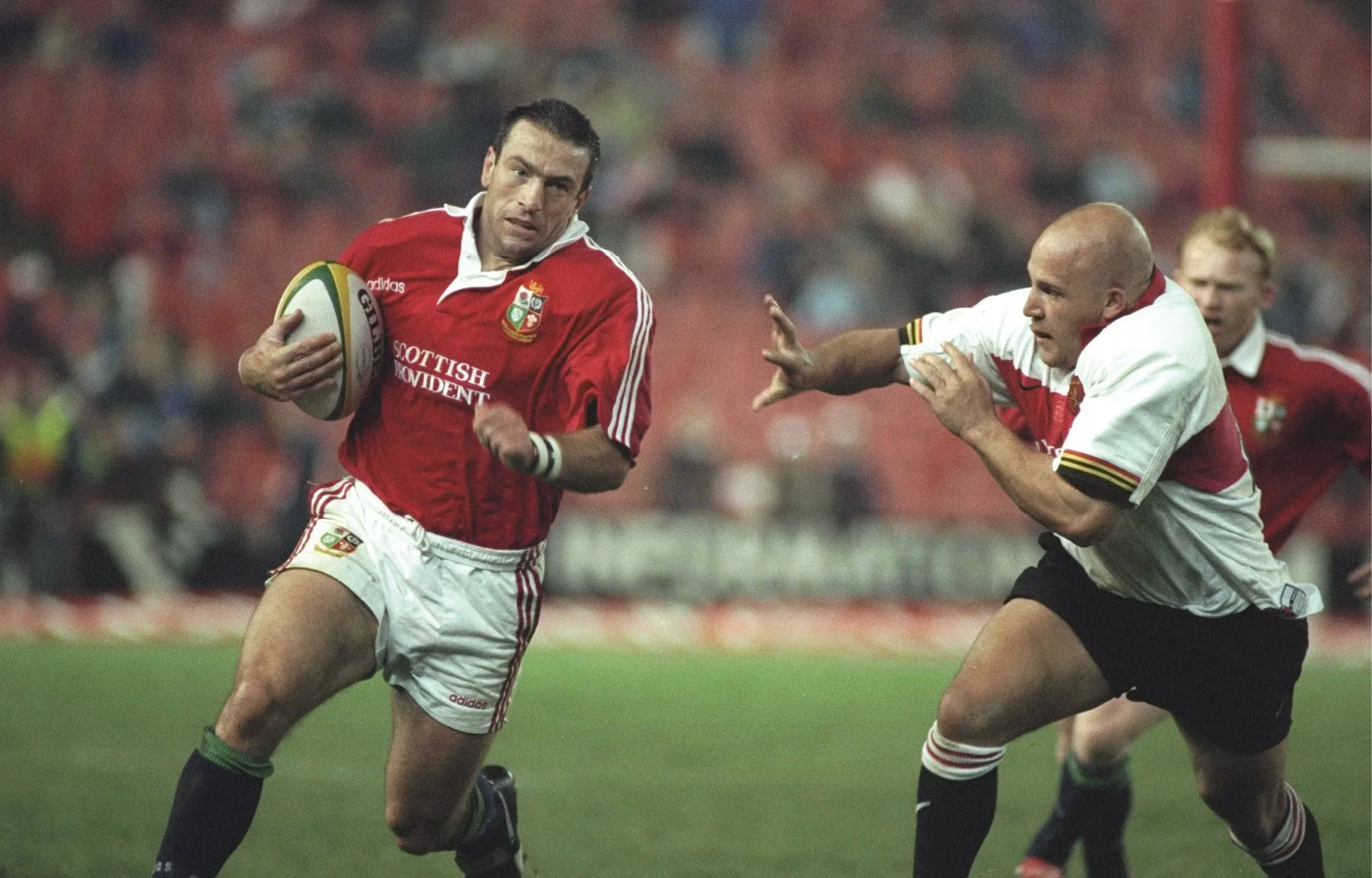

The first headlines came when he faced James Small, the Springbok wing turning out for Western Province. “A rabble rouser, bully,” says Bentos of his wing rival. “He was a big part of that 1995 World Cup win when he nullified the threat of Jonah Lomu alone. I was picked out of position from the right wing to play on the left wing to stand in front of James Small.

“All the focus prior to the game was the threat that James Small would pose throughout the course of the game, and due to a sensational piece of wing play on his behalf and a shabby piece of defensive play on my behalf, he went around me, kicked the ball and it ran on, but Neil Jenkins got back and touched the ball down, resulting in a 22-metre drop out to us.

“James Small then came up to me, goaded me, circling his finger, calling me names. And I could have done one of two things. I can either dig a hole, or get out and fight him. Five minutes later, same scenario, Small receives the ball, full of it, and goes to do the same manoeuvre, this time I took him quite high, he then tries to slam the ball in my face. I ducked. We stepped out of play, and as he lifted me, my forehead just accidentally hit him across the bridge of his nose, and we ended up getting split up. We had a bit of a tussle.”

During a 35-30 defeat to North-East Transvaal [now the Blue Bulls] on the following Saturday, Bentley was replaced in the second half. Knowing full well that being in the Saturday side meant you were in Test contention, being back in the midweek side with just two weeks to go before the first Test, he thought his chance had gone. “I went off tour for three days, I basically laid low.

“I looked at the man in the mirror. Yeah, and actually that was the occasion when I wasn’t comfortable with what I was looking at, you know?”

The midweek game was against Gauteng Lions. “My wife always says to me, ‘you went on one tour, scored one try, and you’ve got one speech, get over yourself Bentley’.

“I can remember every single moment of it, my strength has always been broken field play, kick reception is where you’re at your most dangerous.

“Because,” he continues, “all of a sudden, when a game has turned professional, it’s very defence orientated but on kick reception, certainly on a hack through, you’ve got a disorganised defence in front of you.

Getty Images

“So, Neil Jenkins picks the ball up, but just before that I’d looked up and saw a backrow and a hooker in front of me… 25 metres away, so there’s thirty metres of space on the outside. I’ve called for the ball prior to him getting it, and he’s given me it, so the first bit’s planned.

“I’m going around those two next, finding my space, picking my gap, and then all of a sudden, I’m under the posts, and we score and then we’ve won the game [20-14]. And I’m back on tour.

“That was a moment that changed my world, really, because nobody knew me,” he says. “Yeah, I was playing in a corridor in the Pennines, playing rugby league, then a bit for Newcastle in the second division, so it was, ‘who’s this guy, Bentley?’ ‘Who is he?’ But, all of a sudden, dare I say, when I came back from the tour, because of that one try, and the fact that we won [the series], I was nearly famous, and actually it was a really awkward place to be. I’d never been famous before.

“There were book deals, people ringing me up to do this and do that. I was put in a place that I’d never experienced before and I lost sight of what I was for a short period. I was just a rugby player. I was a boy who started playing at Cleckheaton, finished at Cleckheaton with a little bit in between. I just played rugby.”

He couldn’t sleep the night before Test selection, instead he was found waiting in the hotel corridor by team liaison Sam Peters who was handing out the letters. “I took the letter downstairs, put it on a table in the team room located in the basement of the hotel – we had decided we wouldn’t sit in each other’s rooms, we wouldn’t gather privately, we’d have a team room which was the focus.

“I put the camera to one side, and thought, ‘You know what? This is my moment’. I just stared at it, and it had, ‘John Bentley, British and Irish Lion’ on the front of the envelope. I picked it up and the first word I read was, ‘congratulations’. I couldn’t believe it, I’ve been picked and I thought, ‘oh, who shall I tell first? My mum, my dad, my wife, my children?’. And it went on to read, ‘you’ve been selected a replacement’. I was gutted.”

The first Test was fast and furious, and Bentley never got on, but Ieuan Evans would get injured after the game, opening the way for the boy from Cleckheaton to start the second Test. “The biggest day of my life, 28th of June, 1997,” he says. “Kings Park, Durban, sheer place, 80-90,000 people there, only 10,000 Brits. There weren’t many supporters in South Africa for us. But actually, I think having won the first Test, a lot of people got flights out for the second Test. And we were second best in the second Test, probably for a good sixty minutes of the game, they were unbelievable, the South Africans.

“It was like tanks coming at you,” he says of the Springboks. “I’d worked hard all my life, I really had, and the Lions tour became my time, but that game had been ferocious. There was about three minutes remaining, we were fifteen-apiece, and I remember Guscott demanded the ball from Matt Dawson, received it, dropped a drop goal. It went over, gave us three points. Then three minutes later, the final whistle went, and that moment was probably one of the most frustrating places that I’ve ever been in my life.

“There were just so many places I wanted to be at that one moment,” he continues. “There was all the boys on the pitch, all the fifteen, the lads in the stand who were integral to being successful. And then there was the people that are most important in my life, my wife and my three young children. I wanted to be with them, to share it with them. And then I just remember stopping and thinking, ‘Oh, no, shit, of all the people, why did it have to be Guscott’,” he laughs.

Bentley recalls the speeches of head coach, Ian McGeechan, how in ten, fifteen or twenty years’ time, the players would need only to look at each other, not say a word, but know what they’ve done, what they’ve achieved. Geech’s words were immortalised in Living With Lions, which came out in November 1997, and the first to review the video was Sandy. “It arrived when I was away, and she said, ‘I’ve watched it, and it’s just you being a dickhead’.”

Bentos talks of Doddie Weir a lot: his illness, what he achieved, what a great man, the moments. “You know, when Doddie got injured, I always remember, I’d given him the camera to go to his room, he was packing his suitcase and what have you, and I took the camera back to my room, and I cried because the tour had finished for him. Just like that.”

The one time during several hours together he’s almost brought to tears, is about a party organised for Doddie, who died from Motor Neurone Disease in 2022. “The sad thing was,” he began, his voice struggling, “he missed the party, and he loved a party…”

After the Lions, although he’d earn two more caps – nine years on from his first ones – his professional career began to wind down. “I started to break down a little bit, I had a bit of a fallout with Rob [Andrew, the director of rugby at Newcastle], and what I certainly recognise from that, you can’t beat the boss man, ultimately, no matter how strong and opinionated you are…

“I ended up leaving Newcastle, I went to Rotherham for a short period, which was probably a mistake. It’s nothing disrespectful to Rotherham, but my body was breaking down, and it became a bit of a struggle to look in the mirror, you know.

“I ended up retiring professionally then, and ended up going back to Cleckheaton, which is where I first started, which I left when I was eighteen years old, which I didn’t really leave.

“I stood there as director of rugby for three games, and thought, ‘oof, the only way I can change this, is if I get on the pitch’. And I ended up playing for another twelve years, until I was 45.

“We got four promotions in six years. We were way down, but we ended up on Saturday afternoon on Grandstand. We ended up on the results, yeah, top four divisions, which was a real accolade for a little tiny club, which meant so much to me, which you’re so thankful to for giving me the start.”

Bentos has almost as many mantras as he does anecdotes. “You know,” he says, “life’s like climbing a tree: you’ve got to get to the top of the tree, occasionally you branch off and it bends, and that’s quite exciting. But, now and again, that branch snaps, you are on your arse. Then, you’ve got to get back on the tree.

“I always remember, not long after retiring, stopping playing, I stood in the garden one Saturday afternoon and thought, ‘what you going to do now big shot?’

“Playing professional sport, you become a little bit institutionalised. In a sense, it’s a little bit like being in the armed forces. Not as intense, but you’re told what you got to do, what you got to wear, where you got to be, what you got to eat. And you suddenly come away from that, you exit that and there’s a big void, and the void needs filling. And I got lost for a short period went a little bit bonkers, a little bit crazy.

“I was making poor decisions, hurting the people that are probably the most important people in your life, people who are close to you, inadvertently hurting them, but also recognising that and actually putting things in place to try and recover the situations that you’ve created, but all good.

“There’s not much good about getting old,” he concludes, “and I love talking about family, and I’ve got three beautiful children. They’re all grown up now, but I’m embracing a different chapter in my life and it’s called grandparenting, and I’ve got four and I’ve worked out there should have been a way to bypass the parenting and go straight to the grandparenting. It’s far more enjoyable.”

Story by Alex Mead

Pictures by Russ Williams

This extract was taken from issue 30 of Rugby.

To order the print journal, click here.