Exeter’s County Ground

The Beer Raffle

Clontarf RFC

Freddie Burns

Merthyr RFC

The intoxicating smell of fuel still hung in the air from the night before. Picking their way through broken spokes and burnt out clutches were Exeter RFC’s finest fifteen, making their way to Tuesday night training at the club’s historic County Ground.

It had never been a place to conform to just one sporting discipline, and John Lockyer, who had captained the team from 1970 to 1981, knew this better than most: “You walked through the tunnel, and there were bits of motorbikes and helmets lying everywhere. Then of course, on Saturday, there was the greyhound racing.”

Long before the amateur era of Exeter Rugby, before the speedway and the greyhounds, the circular plot of land situated in the low lying central district of the city, had been occupied by a makeshift wrestling ring and a rickety seating area, encompassed by the terraces and cul-de-sacs of St Thomas. Wrestling had been a very popular form of entertainment in the 1800s, and the first event there took place in 1841, with a prize purse of one hundred sovereigns; a huge sum of money at the time.

Forty years passed before the Devon County Athletics Company saved the acre and a quarter from becoming just another block of brick houses. Snapped up when the plot was listed for sale in 1888, they built a seven hundred seat grandstand, as well as installing an asphalt cycle track that encompassed the playing field. Exeter Football Club, (who actually played rugby) were founded in 1871, and were the first official team to use the ground. Their first game was played against St Luke’s college in 1873, in a field belonging to a Mr Morrison, known as the Militia Field, as it was positioned behind the city’s barracks.

The turn of the century would see the most famous encounter at the County Ground. The first ever game involving a New Zealand touring team was played there, against a strong Devon outfit. Devon, who had forgotten their kit, played in Exeter colours of a white jersey with a black hoop, whilst their formidable opponents ran out in a kit synonymous with their legacy. It was on this day, after fifty-five points to four trouncing, in front of six thousand local supporters, that the All Blacks earned their title.

Sport at the ground was brought to a halt with the commencement of the First World War: it was instead used for military training, and the storage of transportation vehicles. The post-war years would see the replacement of the grandstand, which was lost to a fire in 1918, and the ripping up of the cycle track. It would make way for cinders and shale, as the ground looked to host a sensational new Australian sport called speedway.

The crowds drawn in by the speedway each week were often higher than the attendance seen for rugby on a Saturday. “The Exeter Falcons would have more than ten thousand there on a Monday night,” says John, but this was many years later. Having had their first meeting in 1929, the speedway was not an immediate success. After 1931, the sound of revving engines and screeching tyres was replaced by flying greyhounds, who remained a permanent fixture.

During the second world war, sport was once again replaced by military barracks, as the ground was occupied by the tents of American and British soldiers. Most notably, it became a training base for the US soldiers preparing for the D Day landings. Circa the war, In 1947, speedway racers returned to the ground, and their daredevil antics would remain a regular attraction for the people of Exeter, right up until the ground’s final year.

Despite the popularity of the speedway, one of the largest crowds ever recorded at the County Ground was for the return of the All Blacks in 1963. Sixteen thousand eager spectators spilled onto the gravelled straights and sanded corners of the racing oval, where temporary stands had been erected for the occasion. Amongst them was a young Robert (or Bob) Staddon who today sits as chairman of Exeter Chiefs.

In those days the three sports got along quite harmoniously, but much like the rugby players taking to the floodlit fields on a Tuesday night, the racing dogs were not ‘trained’ to the same professional standards we see today: “It would be true to say that the rugby and the greyhounds didn’t go hand in hand,” admits Bob, “you had to be very careful sometimes, when walking around the pitch.”

The pitch itself wasn’t best known for its quality/ “A quagmire would be a good word to describe it,” says John about the playing conditions. “Visiting teams would often wonder if we’d watered the ground in anticipation for them coming down,” adds Bob.

In 1979, a touring Springboks side defeated a Devon XV captained by John Lockyer, but it was not the inches of mud on the surface that captured the headlines. Instead, the game was overshadowed by apartheid tensions back in South Africa, which saw a huge turn-out of protestors on the day. “I can still remember the line of police that circled the whole ground to stop people running on the pitch to try to stop the game,” recalls John.

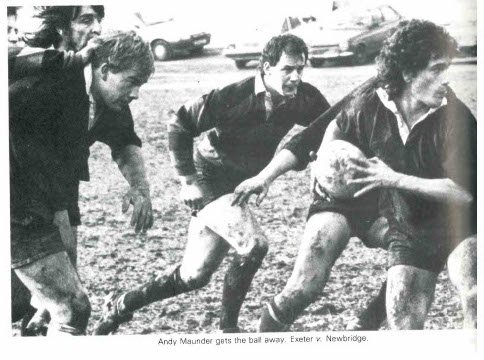

During the same era, many fierce contests took place at the ground, often involving the Lockyers, Staddons, and Baxters of the club: “We had a strong fixture list in the seventies,” says Bob, “we would play Leicester every Easter Tuesday, we had some real tussles.” Then there were the derby games that would attract throngs of southwest supporters throughout each season: “Our major rivals locally were Plymouth Albion, and Torquay.”

As the game transitioned from amateur to professional, Exeter were one club that saw sustained success. They achieved back to back promotions between 1995 and 1997, climbing into Allied Dunbar Premiership Two, the division below National One. In 1999, with John and Bob being two of the club’s four trustees, the rebrand to Exeter took place.

In 2003, the decision was made to sell the County Ground so that they could develop a new stadium that would accommodate their hopes of becoming a professional team competing at the top flight of English rugby. A deal was reached with Bellway Homes, who paid over eleven million for the ground, a sum of money that was Exeter’s ticket into the top flight, enough to purchase the land on which Sandy Park sits today.

Their final season at the County Ground from 2005 to 2006 did not get off to a strong start. A poor string of results saw Ian Bremmer, the club’s first professional director of rugby, forced out. The team’s final performance under him was a strong win against Coventry in front of a home crowd of over three thousand supporters. “We had invited all former captains that day,” Bob tells us, “it was a celebratory black tie dinner that brought rugby at the County Ground to an end.”

Former England under twenties team manager, Pete Drewett, was appointed head coach for the club’s first season at their new home; Sandy Park. In his three year tenure, Exeter went from a fourth place to back-to-back second place finishes, but this was not enough as both Northampton Saints and Leeds made their way back into the premiership ahead of the Chiefs, who so desperately wanted that golden ticket into the top flight.

In 2009, Bob Staddon was asked to step up and manage the professional fate of the club: “I said I’d be delighted to come back, but only if I could have Rob Baxter as my coach.” With Bob’s one wish granted, Baxter took over in the inaugural year of the RFU Championship, and with it came the introduction of a play-off structure to decide who would go up. Exeter finished runners up, and found themselves in a face-off with their near neighbours, Bristol. A tight first leg saw them travelling to the away leg of the fixture with a nine points to six lead, courtesy of Gareth Steenson’s boot. Against all odds, the Chiefs rose to the occasion, defeated their more established rivals 29-10 at their Memorial Stadium, and secured safe passage into the promised lands of Premiership rugby.

The success story of Exeter Chiefs is one to inspire grassroots teams up and down the country. Their rise to the top was no lucky coincidence, but the hard earned product of a community that wanted to see their club be the best it could be. Sprinkled among rich memories of their journey are those legendary battles fought at the County Ground, those Tuesday nights under racetrack floodlights, treading across a minefield of exhaust pipes and carburetors just to play rugby. Bricks and mortar might now stand where locks and half-backs once did, but the echo of the Exeter faithful will forever be heard in that low lying region of St Thomas’.

By Tyrone Bulger