West Hartlepool

Around the corner from Jeff Stelling’s house, in a town famed for hanging a monkey dressed as a French sailor – a town that, ironically, 200 years later voted for a monkey as mayor – is a rugby side that’s lived quite the life. Almost a decade of being a Premiership yo-yo club, ended in four relegations. They lost their home, their coach, their players, their fans and came close to extinction. And yet, somehow, West Hartlepool are still with us.

It’s a rugby club that gets trotted out alongside the likes of Waterloo and Orrell in those lists of often forgotten clubs that were once quite big but have long since been cut adrift to float down to the nether regions of the rugby pyramid.

Except West Hartlepool were never ones to engage in such passive acts as floating. Forever at the sharpest of sharp ends, they were a ‘death or glory’ side all the way. If you’re going to go, go big. If you’re down to your final roll with your last few chips, throw them all down on black six – and borrow a shedload of chips from someone else and chuck them down too while you’re at it.

Their record after being promoted to level two of English rugby back in 1991, reads: promoted [to level one], relegated, promoted, ninth, bottom (but no relegation), relegated, promoted, relegated, relegated, relegated, relegated [level five]. “You were always fighting for something,” says John Stabler, a player and coach of West Hartlepool during the best and worst of times. “It was never boring, you were never mid-table, there was always something going on.”

The same can be said of West Hartlepool. Not everyone, especially southerners, might find it immediately on the map – it’s in County Durham, on the north east coast almost halfway between Middlesbrough and Sunderland – but it’s got its share of claims to fame, and not just Jeff Stelling, whose childhood home, we’re told often during our trip to Hartlepool, can be seen from the clubhouse.

The earliest of the tales goes back to Napoleonic times when a monkey was the only survivor on a wrecked French galleon, and, apparently dressed in a naval uniform, was duly hung. Just in case. Fans of Planet of the Apes probably think the locals were merely taking a precaution for the good of mankind.

That monkey was duly inspiration for the local football club – Hartlepool United – to have a monkey as a mascot. Even monkey mascots have ambition though, and in 2002, H’Angus, duly ran for local mayor. And won. A monkey in charge? The hanging may not have been enough.

Elsewhere, around town and at assorted moments in history; film director Ridley Scott attended the local art college; the comic strip Andy Capp was based on working-class Hartlepool; and ships were once built by the ocean-load here – at its peak, Hartlepool was one of the biggest builders of seafaring vessels in Britain. They kept a fair few too with 236 ships regularly setting sail from the docks. Some locals have felt an unquenchable need for speed with the first Brit to be invited by the American Air Force to fly their latest stealth jet hailing from these parts, and Andy Green, the current land speed record holder (a cool 714mph), grew up in the town. Completing this Hartlepool Walk of Fame, John Darwin, the ‘canoe man’ who faked his own death, also comes from Hartlepool. As does Des Barnes from Corrie. And footballers David and Andy Linighan were born here too, which is perhaps slightly less interesting by comparison.

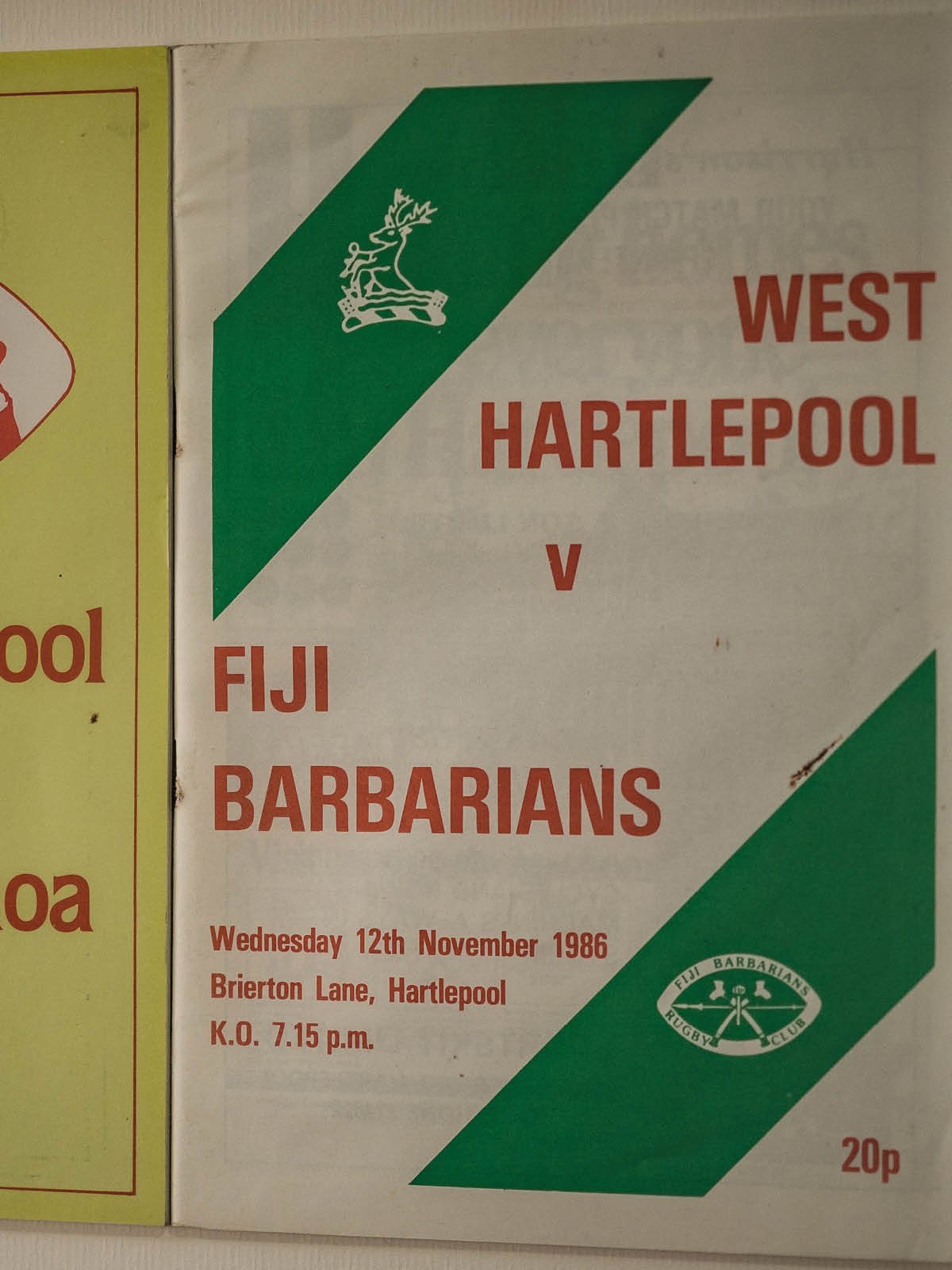

But, once upon a time, the biggest story in town was the rugby club and long before the halcyon days of the Premiership too. At a reunion of former players, on the day the current first XV are facing North One East rivals Alnwick in their latest bid to avoid relegation, many of those glory days are being recounted. At the centre of many conversations is John or ‘Stabbers’ as everyone calls him. He steps away from the heaving clubhouse to talk to us. “The old ground, Brierton Lane, was about half a mile away from here,” he says, pointing in one direction, “and I lived just over the back of it in a council estate.

“The local rag used to list all the players on Tuesday night that were playing at the weekend in each team for West [Hartlepool], and my teacher put me down for the juniors, so I came down. I wasn’t even playing for the club. I was about 14, I think.

“Thing is, that team – from the age of about 14 through to 19 – was one of the best kids teams the club has ever had, we had fabulous players. There was a club called Burnage, nobody ever beat them, and we did. Another local school Ampleforth also never got beaten, but we went when there and beat them too. I’m not trying to give my life story here, but I think this is what made West Hartlepool unique – we were all local lads.

“I was playing in the top league in rugby with my mates,” he continues, “with kids I’d played with since I was 14. The two props; one was my best mate at school, the other went to the school next to us. There might have been one or two people, if that, who weren’t from Hartlepool and surrounding districts, maybe from Middlesbrough or somewhere like that, but that’s it.

“It was like a family, yet we used to play in the Premiership. I know you’d see lads in Richmond and they’d go to The Sun for a beer and have a night together, but you never got the impression they were mates like we were. They wouldn’t ring each other the next day after the game to see if they were going up the club for a pint. That’s what we did, every Sunday we’d all be at the club cracking on about the day before.”

The foundations for West Hartlepool’s league success was laid long before John and his mates arrived in the first team. “While this was going on with the kids,” says John, referring to his own youth side. “Derek Boyd, Paul Stacey, Peter Robinson and the older generation were in the first team fighting their way into national recognition, taking fixtures wherever they could. Les Smith, the fixture secretary, was fighting to get the games against the big sides so the club could make its way around the national game. This was in the early 1980s. And then the Whetton brothers came here.”

Famously, at least in these parts, in the centenary season of 1981-82, West Hartlepool had two All Blacks take to the field in the form of the Gary and Alan Whetton. Remarkable as it may seem, the two All Blacks were recruited personally by a local businessman who wanted to help his two sons, promising young players for West Hartlepool, develop. So, as any doting father would do, he hopped on a plane – or boat, we’re not sure – headed to New Zealand, met the brothers face to face, and they agreed to come to the north east – which was probably not on the bucket list of many antipodeans at the time. “He was a lovely fella,” says John of the businessman. “He had a scrap business and his sons were part of a successful colts side, so to help them and the club out, he brought the brothers over. He put them up and gave them jobs. That was the old professionalism back then, I guess this thing was always happening in London, but it wasn’t happening up here. They were phenomenal players, Gary was already an All Black and Alan would get capped later, both would play in the first Rugby World Cup final. Later, there were two or three other provincial players from New Zealand, they were different class too.

“It really strengthened what was becoming a good team and the whole thing started snowballing into us becoming a really successful rugby club.”

The Whetton brothers arrival stirred up the local rivals too, with Vale of Lune particularly notable in bringing in Jock Hobbs, who captained the All Blacks and later became chairman of the New Zealand Rugby Union.

As fly-half John ‘and his mates’ began to take up key slots in the first team, the league system of English rugby was taking shape and, with that in place, Les didn’t have to beg to get the big games. Instead, with West Hartlepool in National Three, they could pick off the big guns. Promotions followed quickly: three to two; two to one. “The first game we ever had in Courage League One [now the Premiership], we were playing Wasps at home,” recalls John, “and we’d gone from three to two, two to one, quite comfortably, so we thought, right, home game, first of the season, we’re going to beat Wasps, we’re going to beat everyone. They had this flanker called Buster White, an openside, proper hard kid, and they were a proper Premiership class-A side, and they beat us 19-6. I remember walking off, thinking, ‘we got a lesson there, this is different class, this is different gravy.”

The gravy was different, but they soon became accustomed to it. Far from being overwhelmed, they won games, in one season winning as many as six and finishing ninth (albeit in a league of ten). “We went to Gloucester,” says John, “and nobody ever beat them at Gloucester – not Wasps, not Harlequins, none of them won there. But we did. We beat them 13-7 or something. I remember we scored early in the corner in front of The Shed fans and, well, some of them were particularly vocal to say the least.”

Throughout the 90s, West Hartlepool would consistently go up and down between the top two divisions. The only respite came in a three-year spell when they finished ninth one season and were then were saved from the drop due to a relegation freeze at the onset of professionalism. The club’s rise to prominence had, initially at least, made them the hottest ticket in town. “The crowds at the time were probably about 4,000 people,” remembers John, “and bear in mind the football team Hartlepool United were only getting 2,500 back then. I remember there was a time they even changed their game to a Friday night because we were playing on the Saturday.

“There was a local TV sports magazine show called The Back Page and we were on there a few times,” continues John, “and me mam used to record them all and there was this particular game I always remember. We were first and Newcastle were second and both of us were beating everyone and there must have been about 7,000 people at the game. We won and we had something like three games to go and we only needed a point, so we were up.

“I remember watching this recording of the show and it showed maybe 10 to 15 seconds of footage of just thousands and thousands of people coming into the ground. There were about ten people with buckets taking money for entry and I just remember thinking, because nobody was getting paid, ‘why are we not professional?’. Well the reasons would become apparent later, but, at the time, we were successful. The supporters were great, even if we lost, they still saw Will Carling come to Brierton Lane or Lawrence Dallaglio come to Brierton Lane – all coming to play against John Stabler and his mates.”

Times did change, however. At the dawn of professionalism, the Welsh international Mark Ring came in, along with a clutch of Welsh players. “I’d been injured when he came along,” explains John. “I’d been playing against Canterbury, who were touring from New Zealand, and I remember it was a horrible, horrible day, I’d not seen much of the ball and it came skidding out to me and their hooker hit me in the leg, a lot of people told me I wouldn’t come back from it – I think that’s why I did it. I had been thinking that, as I was about 32/33, that could’ve been my time.

“But I got back in the team, I was one of the semi-pros still there, and I learnt a lot from Mark, he opened my eyes a bit on the rugby side, he’s a great guy. But we got relegated that year, Mark got sacked and the club brought in Mike Brewer, the former All Black number seven. He called me in, and said that as I was 34, my time was up.

“It was tough to take,” he admits. “Not because I didn’t think he was right, but because I’d been involved so long I realised it was business now, it was not about this family anymore.

Club president, and former fixture secretary, Les Smith is manning the gate with a slow trickle of cars to keep him half-occupied. Finding a parking space won’t be a problem today. “We take it in turns,” he says of car park duty. We point out to Les everyone says he does it every week. “Well, it’s only a dozen games a season isn’t it?

“It’s just so I don’t have to watch the rugby,” he adds, laughing.

Les first started watching the club in the 50s with his dad, before becoming a committee man in the 70s and then fixture secretary in the 80s – a core part of the team, on and off the field, that laid the foundations for West Hartlepool. “It was a gradual thing,” he says of the club’s rise. “We had a very talented bunch of people who were running the show in 70s and 80s – people with real foresight and drive. It wasn’t just on the field, it was off the field, and gradually players recognised the fact we were a coming force and would join us. We used to take people from Gosforth too, so we had a monopoly of the best players around here, until professionalism came along and, of course, John Hall’s money took them there.”

He recounts the same tale as John: of the Whettons; the scrap businessman and the fight for fixtures against the big guns; the merit table wins and the promotions. He also gives glowing mention to Dave Stubbs, the coach who got them promoted three times, but would never become full-time coach because of commitments elsewhere.

It was the full-time coaches that signalled a change. From an Australian called Barry Taylor who hadn’t heard of famed opponents Brian Moore and Jason Leonard and drove some of his own players to join Harlequins. “We sacked him sometime after Christmas and Stubbs came back in again to finish the season – we were in the Premiership then,” explains Les. And he matches John’s account of Mark Ring: ‘a great guy’, who, many at the club say, was let down by some of the players he brought with him.

Bigger problems came in the decision to not only leave, but sell, their much-loved home, Brierton Lane. “We had to leave,” says Les. “The council wouldn’t let us develop it, so if we had aspirations to stay in the Premiership, then in the longer-term we had to go. We could have stayed in the short-term, but we had to be in the process of developing the ground to accommodate so many seats, otherwise they’d have thrown us out.”

Now into the 1998/99 season, on the field, with Mike Brewer as coach, West Hartlepool once again struggled to make an impact, relegation seemed certain. Rumours abound that Worcester had offered to buy their stake in the top flight and also paid £65,000 for first dibs on their players when they went down. But the bigger ramifications were off the field, something even the club mascot was aware of when he staged a half-time, sit-down protest in the centre circle. Now playing at the local football club’s ground, the crowd hadn’t followed and it was leaving a gaping hole in the finances. “The gate money didn’t add up,” explains Les. “We were getting 1,000, maybe 1,500, but at Brierton Lane the bigger gates were 4,000 and it would always be at least 2,500. It was dramatic, we gave away a lot of freebies too. Maybe it was the matches being on Sundays, maybe they were sick of watching us, maybe it was the novelty value of playing big teams or maybe it was the local connection had been lost because there weren’t local boys in the side anymore. People used to travel from all over the north east to watch us, but even within the town we’d lost support.”

And then? “We went bust. It was the year the Premiership voted not to go into Europe, but we’d already worked that into our budget and then the brewery called in a loan they swore they never would.

“We owed £600,000 to various people,” he repeats. “It became a CVA so we paid so much in the pound back, but it meant we had no money.

“Mike stayed until the end of the season,” explains Les, “he’s a very good bloke, he said he’d stay but he’d have had no budget.”

And so they turned to ‘Stabbers’, who’d been player-coach at Redcar in his time away, earning two promotions there in the process. “They knocked on the door and it was tough,” admits John. “They were in Premiership Two by name only, they had no players, no ground, no club, nothing. In the local press they were writing about the return of the prodigal son and that everything was going to be alright again – it was never going to be alright again.

“It wasn’t just that we had no money, we had no means of making money or borrowing money because we had to pay the debt back. At the first training session in July, I had four players and we were meant to be kicking off the league season against Moseley in August. It was impossible really. The next session we had three – the only plus side was that they were different from the previous week, so I figured I had seven players in total!”

Scraping around for local lads, John managed to get together a young side to make up a XV. ‘They were good kids, but not good enough for playing in the second best rugby league in the country,” he admits. “I don’t know how we did it but we got a side for the first game at Moseley and we only lost 19-0 – it felt like a win. It was the hardest time of my life, but the best time of my life – we even won a game that season, Orrell away, I don’t how we did it.”

Relegation followed. “All the players left and so we had none again,” says John. “This time we got a nucleus of lads, about nine or ten of them, and each season we’d add to them. They were always playing three leagues higher than they should’ve been. We’d go down to London, get whacked, and 20 minutes afterwards they’d be laughing and joking in the bar. They didn’t really understand this level of rugby, and it’s a good job, that’s why they stayed at it.”

With no money on the field, relegation followed, they were in freefall, out of the national leagues and into the regionals – never pausing to take breath. “We just had to keep the kids motivated, making them laugh,” explains John. “We’d get five or six on Mondays and Tuesday for training, then 12 for a team run on Thursday, but that was how it was and we got through it. I was determined we wouldn’t die, and that the next Saturday we’d get a team out.

“One year towards the end we didn’t get relegated [now in North 1 and finishing 6th], and it felt like we’d won the league. It was fabulous, even though it was horrific.”

Off the field, the club were trying to make ends meet and find a home. “It was the same committee men, like Les, who’d got us up to the top and they were still with us, they could easily have walked away,” says John.

As if fighting for survival on all fronts wasn’t enough, there was also a feeling that support within the town hadn’t just dwindled but almost turned bitter. “Apart from 150 fans who were always there shouting and screaming for us as we were getting hammered every week, it felt like some people didn’t want us to survive,” reckons John. “They’ll deny it, but they all thought West Hartlepool was dead and we should hurry up and die. The lads even got laughed at when they went into town, people shouting ‘got beat again, did you?’. We certainly took a few bullets but we weren’t dead.”

Off the field, the club was literally rising from the ashes, after a season to forget at the ground of local rugby rivals, the club took up residence at a pitch belonging to the local sixth form school – complete with a burnt out hockey pavilion.

As they went about restoring the pavilion for changing rooms, they’d roll out barrels of beer to form a makeshift bar every weekend - ensuring they were rolled back before the school kids returned on Monday.

“The rot stopped because our mini and junior set up had always stayed together,” explains Les. “They’d just been playing out of another local club and once we got the ‘clubhouse’ presentable by adding some portakabins, they moved back and it proved to be our salvation, it meant we had a supply of local players again.”

In 2012, they raised enough funds to build their own clubhouse on the same school site now under a 50-year lease. They lose to Alnwick on the day we visit, one of 18 defeats in the 2017-18 campaign and are relegated to level seven. But it doesn’t really matter, the club are finally stable. Professionalism is a world away and not a place they’re intending to visit again.

Parting words before we let John, now very happy in his role as former player and ex-coach, join the old boys drink-up. His greatest achievement at the club? “Existing,” he responds.

Story by Alex Mead

Pictures by John Ashton

This extract was taken from issue 3 of Rugby.

To order the print journal, click here.