Yorkshire

In 1987, Yorkshire won the county championship with a side flush with British Lion-class talent from Rob Andrew and Peter Winterbottom to Rory Underwood. Today, while the talent remains, the White Rose is still to truly bloom in rugby’s top division.

It represented much more than a name change when Sir Ian McGeechan announced the re-branding of Leeds Carnegie to Yorkshire Carnegie in 2014. The vision was of a club for the whole county, a final chance to establish elite level rugby in Yorkshire by uniting its resources under one collective banner. A nice idea, but perhaps a few years too late. Had they done it at the height of the Phil Davies era, of cup finals and Europe, then maybe it would have been different – then, they were definitely the best in Yorkshire. But in 2014 they weren’t even the best Yorkshire team in the Championship. Both Rotherham, formerly of the Premiership themselves, and Doncaster were above them in the table when the announcement came.

And so that vision failed, and dramatically so. Long-standing parochialisms did their damage and five years later the club was teetering on the edge of financial ruin. Now, having been consigned to relegation at the end of the 2022/23 season, the self-appointed last hope for Yorkshire find themselves in the fourth tier of English rugby, their lowest position in the pyramid for thirty years.

They haven’t been Yorkshire’s only casualties in recent years. Hull, also of National 1, were relegated alongside Leeds; Rotherham now play their rugby in National 2 North; and Harrogate, in both the men’s and women’s, have seen their first teams relegated this year. With this simultaneous demise, the promise that Carnegie once symbolised now feels further away than ever.

It’s been over twelve years since the Premiership last had Yorkshire representation, and aside from an unexpected title charge in 2021/22 from Doncaster, which was followed by sixth place and almost fifty points off the pace this season, Yorkshire’s rise to the top remains on hold.

Next year, Doncaster hope to do better, they have a ground and everything in place to get promoted, but will need luck with injuries, and the small matter of wealthy Ealing Trailfinders to get past.

But, that’s for the new season; today, it’s county taking centre stage at Castle Park as both Yorkshire’s men and women are playing at home, to Cheshire and Leicestershire respectively.

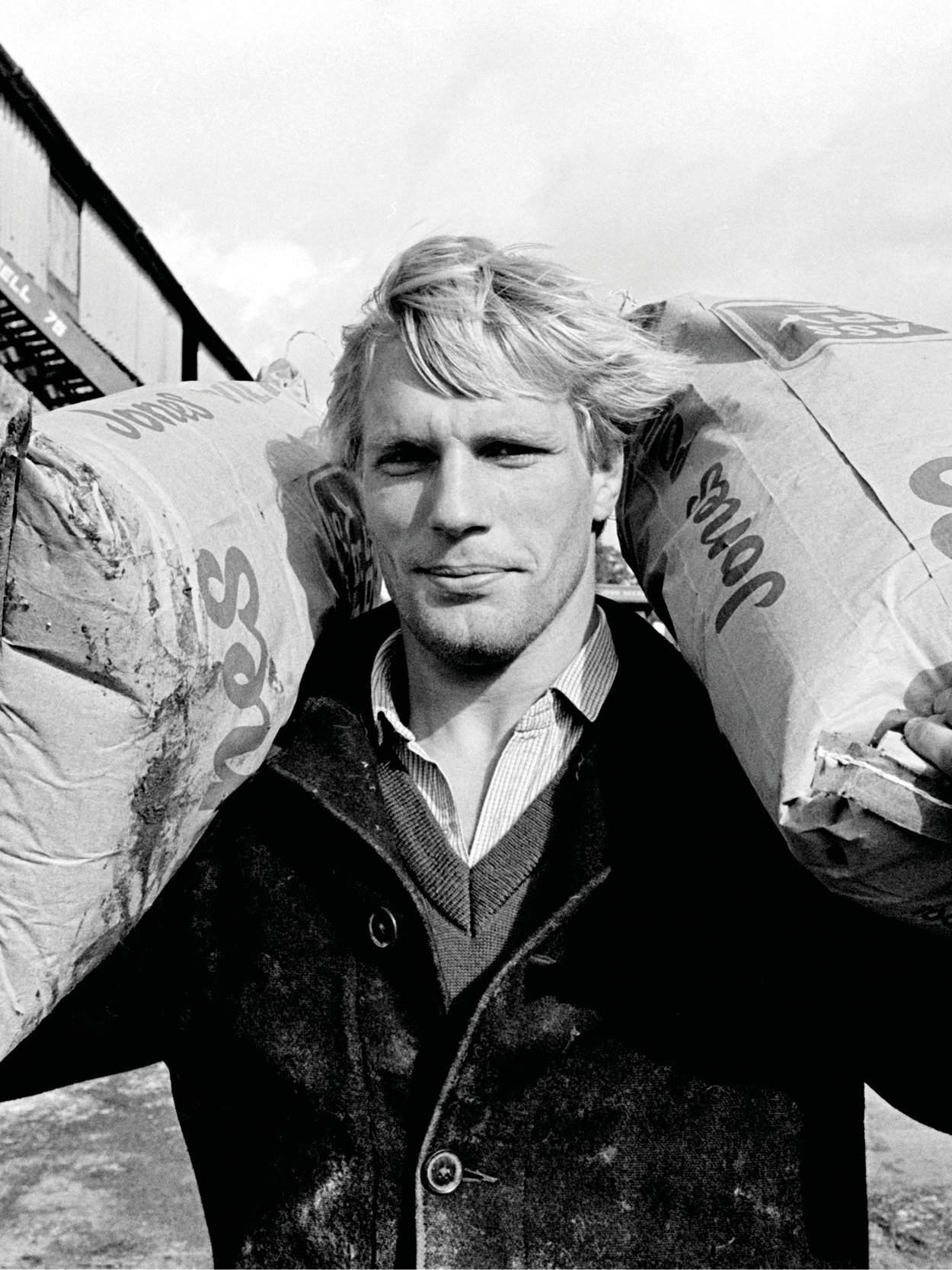

A modest crowd of spectators begins to gather for what is the second round of the county championship for both sides. The difference between eras not just for Yorkshire rugby but also county rugby can be stark. When they took the title in 1987 [beating Middlesex 22-11], they fielded the likes of Rob Andrew, Rory Underwood, Peter Winterbottom and John Bentley, but today, as per the rules, it’s level three players making up the bulk of the starting fifteens.

Despite the obvious rich vein of talent, rugby union in Yorkshire has never reflected the sum of its parts. It’s a sad state of affairs for a county long associated with greatness in the sport – around one in seven of all English-born, full mens internationals for England have been born in Yorkshire. But this trajectory has been a long time coming. Despite flirtation with the top tier Yorkshire has never fulfilled its potential on the club scene, the breadth of talent never concentrated enough to mount a serious challenge up the leagues.

Yorkshire is a talent hub not just for some of the greats of union – from Jason Robinson to Ellie Kildunne – but also for the country’s greatest athletes, so much so that had Yorkshire competed alone at the 2012 Olympics they would have finished twelfth in the medal table, sandwiched in-between Japan and Iran. Perhaps this shouldn’t be surprising given the population is almost five and a half million, virtually equal to Scotland, but regardless, sport of almost every shape is excelled in here. In the egg-shaped variety, they’ve even managed to shine in both codes. Rugby league may have nailed its colours to the M62 corridor and be synonymous with the white rose, but union is still present in all corners, from the glacial grandeur of Wharfedale to the charming Scarborough seaside.

That said, league rugby has never been where Yorkshire has flexed its union muscles; instead, its strength has come to the fore in the county championship. “It was the only way that rugby people in the county pulled together,” recalls Peter Winterbottom, the former England, Yorkshire and Headingley player and current director of rugby at Esher. Peter remembers first playing for the county in 1981 before lifting the championship trophy in 1987, ending the county’s 34-year wait. “Yorkshire rugby has always been parochial; the clubs don’t particularly like each other,” he continues. “But the county championship was one of the few times that we actually all pulled in the same direction.”

That class of 1987 was made of players from the then top table of clubs – Wasps, Leicester, Saracens, Wakefield, and Orrell – a coalition that drew together players from twelve different clubs to unite under the Yorkshire banner. Admittedly, these were the days, albeit few in their number even by that time, when the county championship was still a significant competition and the primary springboard to international honours. “You have to remember at the time there were no leagues,” says Peter. “There were merit tables, but they didn’t really mean a great deal, so the only competitive rugby you got was the county championship. The club rugby in Yorkshire wasn’t as strong as the other regions – we’d go and play Leicester and play Gloucester, but realistically, they were always better and bigger clubs. We [Headingley] weren’t a big powerhouse club, in fact there were none in Yorkshire.

“The likes of Otley, Roundhay, Wakefield and Headingley and more were producing good players, but a lot would leave and go elsewhere, go down south or to London to work. And so, the Yorkshire clubs themselves could never compete with the big clubs in the country – but we could at county level.”

For a people who see themselves as Yorkshire first and English second, the county championship always lit a fire in their bellies. “If you took the London division or the Midlands division, I don’t think they ever had the same sort of passion that the North did, that’s what made it special. Cornwall certainly took it seriously, they were similar to Yorkshire in that they didn’t have any big clubs, but for Leicester, Middlesex, Surrey it just wasn’t the same. The county system and the divisional system was the way we could bring the sort of passion that someone like Leinster or Munster bring to the game now.”

Given the success Yorkshire has had when they’ve joined forces, fifteen titles to be precise, a record bettered only by Gloucestershire and Lancashire, you can begin to see the rationale behind McGeechan’s Carnegie project. However, although well-intentioned, the project was based on naïve over-ambition. “On the face of it, it was a good idea,” says Peter. “It was the only chance Yorkshire ever had of having a proper Premiership side, but people weren’t prepared to go and watch it. It all came down to whether they’d be able to generate enough revenue and income to sustain professional rugby, but they didn’t get the crowds at Headingley that they’d hoped for.”

“There’s a lot of rugby people in Yorkshire, but you wouldn’t get people from Otley or Wakefield going to watch Leeds, you just wouldn’t. My brother played for Headingley then went to Otley, but he’d never go watch Leeds. I’d ask him, ‘why didn’t you ever go and watch?’ and he’d say, ‘well, I’m Otley, I’m not going to watch Leeds’. So, you struggle really to attract the support necessary to sustain a professional Premiership side. But in the old days with the county championship, you would go and watch Yorkshire.”

The advent of the professional era and the demise of the county championship meant the North was hit hardest. Northern clubs have since struggled to compete at the top end of the domestic game. Only twice since 1995 (Newcastle in 1998, Sale in 2006) has a northern team triumphed in the Premiership, in both cases with hearty thanks to well-financed support from Sir John Hall and Brian Kennedy respectively.

Talk of a northern super team combining the two clubs has simmered after Sale’s recent run to the Premiership final; club rugby has largely failed to live up to expectations, perhaps this was the way it always should have been? “But you do sort of feel there’s still the potential there in the Yorkshire clubs,” says Peter. “You look at Doncaster, but do they get enough crowds? Would they generate enough crowds if they go into the Premiership? They’ll probably get a couple of thousand people every week, but that’s not going to get you very far. To really push for the Premiership, they’d have to spend a few million on the team for starters. It’d be great to have a Premiership side in Yorkshire, it would be fantastic, but is it doable? It’s a big gamble for anybody.”

In many ways, the reasons behind the recent misfortunes of Yorkshire’s clubs are the same as those felt across the country – namely, funding and lack of players. However, the county’s long-term difficulties run deeper than most, largely on account of the need to compete for eyeballs in rugby league’s heartland. As a result, Yorkshire’s grassroots have felt the symptoms of the past few years even more acutely. “We have 90 clubs at the moment operating on a Saturday, and there are a number of midweek Wednesday clubs too,” explains John Riley, president of the Yorkshire RFU, as we speak before kick-off in Doncaster. “To put that in perspective, we were down at Hertfordshire with the Yorkshire side on the weekend, they only have something like 32 or 33.”

John was elected president last year but has been involved in Yorkshire club rugby for almost sixty years, by accident he says, after a friend asked him to fill in for Yarnbury RFC on a Saturday as a fifteen-year-old.

Given its size, Yorkshire has many times more business than other counties and yet John reveals there is no equitable funding from the RFU, a problem that has only gotten worse with the pandemic. “Clubs are definitely struggling, there’s no doubt about that,” he continues. “The counties usually would have an allocation from Twickenham of x amount, which we distribute evenly across the five districts. Now, that’s dried up massively from what we used to get.

“It’s affected rugby in Yorkshire mainly through the lack of coaching support,” he continues. “We had a number of regional development officers and coaches which the RFU funded. That’s what is now not there.

“I still think there is something in the back of the mind of the RFU that rugby union ends at Leicester and that the rest of us are involved in rugby league. The first time I went down for a training day at Twickenham, one young lady had given a lecture and she honestly thought there was no rugby union beyond Leicester. And there were representatives from Yorkshire, Cumbria, Northumberland, Durham, and Lancashire there, all up in arms about the naivety of somebody to actually say that. Of course, it’s actually the other way around – there’s more union than there is league.”

With the popularity of each code, many grassroots players in Yorkshire choose to play both, switching back to league as the season gets going towards the end of February. This crossover period has always been a challenge for Yorkshire clubs, but with depleted player numbers after the pandemic it’s another juggling act that has become more challenging. “We will always have that conflict between league and union in Yorkshire and Lancashire,” explains John, “but it causes problems because now many union clubs are actually reliant on league players – when the league season starts, they’re suddenly short of players, so they have to put out one team rather than two. It’s the community clubs, below the national level, that this affects the most.

“Every club across the board, more or less, has lost at least one, most have lost at least two sides since covid. Even the big sides like Otley are only putting out one side, and that’s in National 2. Similarly, Wharfedale have been reduced from five sides down to two.”

This conflict has led to catastrophe for some clubs. “Three clubs in Yorkshire have gone out of existence since covid – that’s Old Groveians, who only have enough to play on the sevens circuit, Yorkshire Main and Wibsey. Wibsey was the club of an ex-England captain, John Orwin – the clubs of England internationals are disappearing.”

In 27 years involved at Wibsey Rugby Club in Bradford, Steve Brooke held just about every post possible. First joining as a player at fifteen, Steve then found his calling in the administrative side and was the driving force behind the club as chairman and honorary secretary. “I’m absolutely gutted with what’s happened,” says Steve, “but I didn’t have time to try and get it back up and running because I’ve got to look after my mother now. I told the director of rugby that I was going to step back a bit, but he told me the best bet was to step away completely or everyone will still think I’m going to do it. Life just gets in the way I suppose.

“Covid had a massive amount to do with it, you couldn’t get any sponsorship in, and people found other things to do at weekends. We just didn’t have the bodies and the bums on seats quite simply. Once you’ve had eighteen months off and you’re not getting beat up every week, it easy to give that a miss.

“It’s nearly all rugby league in Bradford,” Steve explains. “There’s probably only three union clubs in the whole city. There’s at least ten, eleven league clubs in Bradford alone, and we’ve got Bradford Bulls at the bottom of the road. So as soon as the crossover starts you lose six or seven players, and for clubs like us that made a massive difference. It used to be around April time, so it was only a few games, but now they need a pre-season.

“The funny thing is we were actually doing alright before covid. We won the league two years on the trot, winning Yorkshire Five and Four. We were third or fourth in the league and then it all kicked off.”

There are loose plans to re-group in a few years’ time, but with the likes of Steve out the picture it’s going to be a different Wibsey that rises from the ashes.

When the curtain closes at Doncaster, it’s been a grand day out for Yorkshire. The women’s side may have lost to Leicestershire 19-40 but as they are the Division One holders there is plenty they can take from the game, particularly their fast start with two early tries. For the men, it couldn’t have gone much better. Wrapping up the bonus point before the half-hour mark, a stellar performance from scrum-half Sam Pocklington led them to a merciless 87-19 victory. And while the happenings on the pitch provided more than enough entertainment, you couldn’t help but notice a man in a Yorkshire tracksuit frantically shuffling up and down the touchline, still rallying his side and giving orders despite the disparity on the scoreboard. Pete Taylor, Yorkshire men’s head coach, doesn’t see why he’d be any other way. “I want us to strive to be the best we can be, that’s what rugby is,” he says, as players and families gather together after the game. “It’s easy to say after looking at the score lines, but if you just play the basics well and make fewer errors, with our individuals we’re going to do well.” A former Yorkshire player himself, Pete and his fellow coach Dan Scarborough, formerly of Leeds Tykes, are desperate to take the county back to Twickenham having won the competition on the field together in 2000, beating Devon in extra time. “If we can beat Lancashire next week and go to Twickenham, that will top anything for me,” says Pete. “Going as a coach would be far bigger than as a player – I can’t put my finger on why, but it just would mean a lot more.”

After today’s result and last weekend’s 19-70 pasting of Hertfordshire, their chances of a first final appearance since 2008 were looking good. But then, defeat to their arch-rivals Lancashire put paid to this season’s bid, although things are still positive. “Yorkshire will always be a strong county,” continues Pete. “There’s a brilliant Championship setup here at Doncaster, and then you’ve got loads of clubs in and around National Two. So, trying to select a Yorkshire team is now probably more difficult that it was 30 years ago when I was playing.”

His positive attitude is a breath of fresh air and an important reminder that while Yorkshire’s quality may not be visible in the form of a Premiership club, that doesn’t mean it’s not there. In fact, he’s adamant that shouldn’t be the barometer. “Rugby is a professional business now,” says Pete. “It’s just complete circumstance that there isn’t a Premiership club in Yorkshire and I don’t think we should think about it in any other way. The academy is doing really well, they’ve had a fantastic year getting four lads in the England squad and another in the Scotland setup.”

Two of those, Tom Burrow and Tye Raymont, have recently signed contracts with Sale Sharks, joining up with academy graduate and breakout star Tom Carpenter. On the women’s side the talent line is even stronger – no less than four Yorkshirewomen, Zoe Aldcroft, Ellie Kildunne, Morwenna Talling and Tatyana Heard, were part of England’s run to the World Cup final at the end of last year.

“Most people would then suggest that Yorkshire needs a Premiership club, but there’s got to be significant investment and whether that happens or not, it’s not in the county’s control.”

Judging Yorkshire’s success on Premiership status is to ignore what actually keeps a club in the top tier – cash. The fact there are no Yorkshire clubs at that level – men or women – is an indictment of the lack of investment in the game rather than a lack of good rugby players. “It depends what people determine as doing well,” considers Pete. “If you’re looking at numbers of people playing rugby, especially in the juniors, there’s a lot of people in Yorkshire. If you look at volunteers and the striving clubs, you’d argue that Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cheshire, the north of England are doing well. The biggest thing I’m seeing is where clubs are offering more than rugby: they’re offering childcare, bring your family, it’s not just a bring the lads culture anymore”.

Pete’s fidelity to the county game is clear in both his tone and his manner. He’s aware the competition has changed from what it used to be, but he believes it still has an important purpose. “The county championship is a community programme where those players at the top end of the community game get to play for their county. It’s a reward or an experience for these players, and the players that come want to play. It’s not a stepping-stone to anywhere, it’s just a group of lads that want to go and put on a Yorkshire shirt. Yorkshire has a lot of history with the county championship, like Lancashire and Cornwall, so if you asked most players in Yorkshire, they’d want to play for their county. Look at Rob Baldwin today, he’s played professionally at Leeds Tykes and he still sees it as an honour to put on a Yorkshire shirt.”

As the Yorkshire faithful depart back to each corner of God’s Own Country, it’s a chance to take a step back. When we stop looking at rugby as one great monolith and take a closer look at Yorkshire’s individual parts, the white rose is still blooming.

Story by James Price

Pictures by John Ashton and Getty Images

This extract was taken from issue 22 of Rugby.

To order the print journal, click here.