Sir Gareth Edwards

In 22 seconds, the ball went from one end of the pitch to another, passing through the hands of eight Barbarians, with jinks, dummies and attempted decapitations in between. It was the try, one that will never be forgotten, just like the man who scored it, Sir Gareth Edwards.

“Anyway,” continues Maureen, “the cat was always bringing in these birds of all sorts of different colours, and I kept telling the neighbour he must have a hole in his aviary, but he wasn’t having it. He was thinking the cat was digging them up. But, sure enough, one day he came over and said, ‘you’re right, there is a hole’.”

Maureen Edwards is the nan we all we want. Every anecdote she tells is full of colour, in every sense in the case of the tropical bird murders. She provides tea with Welsh cakes pretty much on arrival, continually topping up, and urging us to take the last cake on the plate. What’s more, due to a bountiful apple harvest, she’s also loaded us up with a big bag of apples from the garden – and we’ve only been here ten minutes.

After greeting us at their Porthcawl home, husband Sir Gareth Edwards is equally welcoming and full of stories, even ones he’s had to tell a thousand times over, starting with the tale of that try. The only try in the history of rugby that should almost copyright the use of an emphasised, or italicised, that as a suffix.

It’s been 50 years since Gareth scored it, coming at the end of the most flowing, twisting and turning, jinking and jiving Barbarians move. Despite it coming a good 30 or 40 years before we even talked of things “going viral”, it went viral in the memories of rugby fans the world over. And even for those that weren’t born at the time, including this writer, the try has enjoyed permanent residence in our memories from the moment we first saw a replay.

Gareth, the man who completed the epic move, is pretty familiar with it too, although he has to split the memories of the match itself, to those from the replay. “I watch it every day,” he laughs, “no, I’ve got a video over there and it depends if someone comes along really, the kids or grandchildren want to watch it. Or I might just have a look at it to remind myself what happened really. It was improvisation, it was reading the situation and the vision of the players.”

To recap, the move began when New Zealand wing Bryan Williams kicked deep into the Barbarians’ half with Phil Bennett chasing back to scoop the ball up yards from his try line. “The beginning of the match was a bit of a mess,” recalls Gareth, “kicking here, kicking there, nothing was happening, so when I saw the ball go deep and Phil scurrying after it, I thought, ‘Oh, thank God for that, I know Phil’s got the sense to get it into touch’. Because that’s what the game needed, for the game to stop, and then restart.

“I’d been running one way, then I was running back the other way, then back the other way,” he continues, “and of course Phil got it and started doing the jinks and things and I remember vividly saying, ‘what the hell is he doing now?’. He did something I didn’t really expect him to do.”

Having had his back to his opponents, Bennett had curled back, stepped, stepped, stepped again, then stepped again, sending two players, four players in opposite directions, feeding JPR Williams. “You’ve got Phil jinking, JPR almost being decapitated, then John Pullin in the movement and the ball still managing to get to John Dawes. At this point, all I’m doing is just trying to make a point of being y’know offside, so it can all go past me.

“And then, as the ball goes past, I’ve turned around and thought ‘oh, I’d better get there otherwise they’ll be complaining, saying, ‘typical, nowhere to be seen Edwards’.”

Captain Dawes had dummied his way through, fed Tom David to take the ball into the All Blacks’ half. “Then when I got into the pace of it, I started chasing where the ball was going and, it’s difficult to explain, but you could sense with the crowd too, that something was happening,” he says. “As I looked on I could see when Tom and Derek [Quinnell] continued the movement, I was really having to turn the speed on to get there, and I shouted to Derek in Welsh, throw it here... then it was just a run for the line.

“I suffer from hamstrings though,” he adds, “and I remember thinking ‘please God, don’t go now’, but by that time the roar of the crowd was pushing me on.”

The try was only in the opening moments of the game, it had taken 22 seconds from Bennett picking up the ball to Gareth putting it down, and the Barbarians went on to win 23-11. “You know, you’ve got to understand a little bit of the psyche behind the whole thing,” he continues. “There was even an argument about the composition of our team, New Zealand weren’t happy, that they were facing [effectively] a Test team – ‘oh, it’s a fifth Test, it’s not fair’.”

As was par for the course for the era, New Zealand were on a 32-match tour, and this was match number 28. They’d covered America, England, Wales and Ireland, with Tests against Wales [they won 16-19]; Scotland [another win, 9-14]; England [same, 0-9] and Ireland [a 10-10 draw], and France was still to come, three more tour games and a Test [they’d lose 13-6]. “We [Wales] should at least have drawn,” says Gareth, “at the very least. Phil Bennett’s last penalty just scraped the post; that would have drawn it, and JPR believes to this day that he scored. That’s the difference between then and now, the referee had just said: ‘no, double movement’ or whatever, but JPR is still adamant.”

Gareth pauses, stopping to give himself time to search for more memories, and no sooner has he found the one he was looking for, than he’s found the one next to it too, the Wales match and an indignant JPR a case in point. “I’ve got a lovely photograph somewhere in the archives,” he begins, “of Phil Bennett kicking and there’s the scoreboard in the background and it’s one of those old ones where a man had to actually change it, and you can see the anticipation on the scoreboard guy to drop the score to 19-19, but he never did.”

The backdrop to the Barbarians game was the 1971 British & Irish Lions series win in New Zealand, still the only time the feat has ever been achieved by the famous touring side. “We came back heroes from New Zealand, we were wined and dined up and down the country,” says Gareth. “Maureen and I were driven in a vintage Lagonda to take us up to the village from Neath station. It’s only about 11-12 miles from Neath to my village, but village after village after village, there were people crowding the pavements all the way, bunting on houses, it was incredible. We’ve got some photographs here somewhere.

“And then there was a reception in the local cinema which could probably hold, what, a thousand people Maureen?” “Maybe 500,” she responds from the next room, where she’s been conducting a tour with the photographer. “Barry John, Gerald Davies, they all had the same reception too,” continues Gareth. “It was only when all this happened that we realised the impact we’d had back home really, because it wasn’t like today, when you could see games on the telly from Amsterdam or Argentina of whatever, and back then you didn’t even call someone direct, you had to ring up the operator to ask for a one-to-one call.

“We got letters and there were the newspapers, but they’d be talking about the Wednesday game and we’d already have played the Saturday one.

“But when we got home, people were saying they used to get up at three in the morning to listen to the radio, and everyone wanted a piece of it.”

The Barbarians, laden with Lions tourists from New Zealand, represented a chance for the home fans to get a taste of the series win, albeit with the heroes in a different kit. “All we wanted to do was beat the All Blacks, especially after all the attention the game had had,” he says. “And anyone who knows the Barbarians, knows they have a way of playing, it’s a celebration, it’s not a Test match, even though it might have international players.

“The fascination for me, when I look back,” he continues, “is the fact there was no preparation. We didn’t have a coach, so we asked if Carwyn [James, the Llanelli and 1971 Lions coach] could come along. They [the Barbarians committee] had a pow-wow, and then after much deliberation said, ‘okay, you can have Carwyn but he’s not to go on the field’.”

The preparation was minimal, they’d met on the Friday, had a run-out in Penarth, and a few beers in Pontypridd. There’d been injuries too, Gerald Davies had pulled a hamstring in Penarth, meaning David Duckham switched wings and John Bevan came in, even Gareth’s room-mate Mervyn Davies – a giant for the Lions – had pulled out in the morning with flu, meaning Derek Quinnell switched to number eight. “So you don’t know what would’ve happened if there’d been different players on the pitch,” says Gareth.

Before the game, there was a haka, but not as we know it. Today, it’s a fearsome, well-drilled statement of war where men chiselled from toughest Pacific volcanic rock send tremors through the ground, putting fear into lesser opponents, but then it was a poorly co-ordinated stumble through a series of moves the sequence of which only one member of the team appeared to be vaguely familiar with. “Ah, the haka,” says Gareth, “to be honest, after being in New Zealand for three months, we could do it better than they could. We’d laugh about it really.”

There had been so much time still to play in the game, that the moment that sticks out for Gareth isn’t a try at all. “We knew there’d be a reaction from the All Blacks, and there’s a moment when they’re coming, coming and coming,” he recalls, “and Ian Kirkpatrick, who I rated as one of the best, dived over to score but [Irish prop] Ray McLoughlin, just got in his way and Kirkpatrick landed on top of him. Ray was so strong, and even the great Kirkpatrick, a prolific tryscorer, couldn’t ground the ball. So, for me, that could’ve been the time. I said it when Ray was alive [he passed away last year, aged 82]: while you may celebrate the try, his contribution is every bit as important.”

They did of course hold out for a 23-11 win, with Fergus Slattery, Bevan and JPR adding tries to Bennett’s two conversations and a penalty goal. “That try didn’t win the game,” says Gareth, who it’s easy to forget due to his easy company is actually Sir Gareth Edwards, having been given a knighthood in 2015. “But it was as if the people had come to celebrate that Lions win, and it was the first time the British & Irish Lions had been together [since returning from the tour].

“When I scored all I could think was, ‘I wish that was the last minute, because there’s going to be a reaction’.

“In the end, it wasn’t just the fact we’d won, it was the way we’d been able to play it, and it was the way the Lions had played on tour. Carwyn James had been a big influence and he’d said to Phil, as he was taking to the field, ‘just play like you do at Stradey’. Hence the reason he did all that... But I actually think the win began on the Friday when we met and came together, and regenerated the spirit of the tour,. Maybe those couple of beers in Pontypridd pulled us together.”

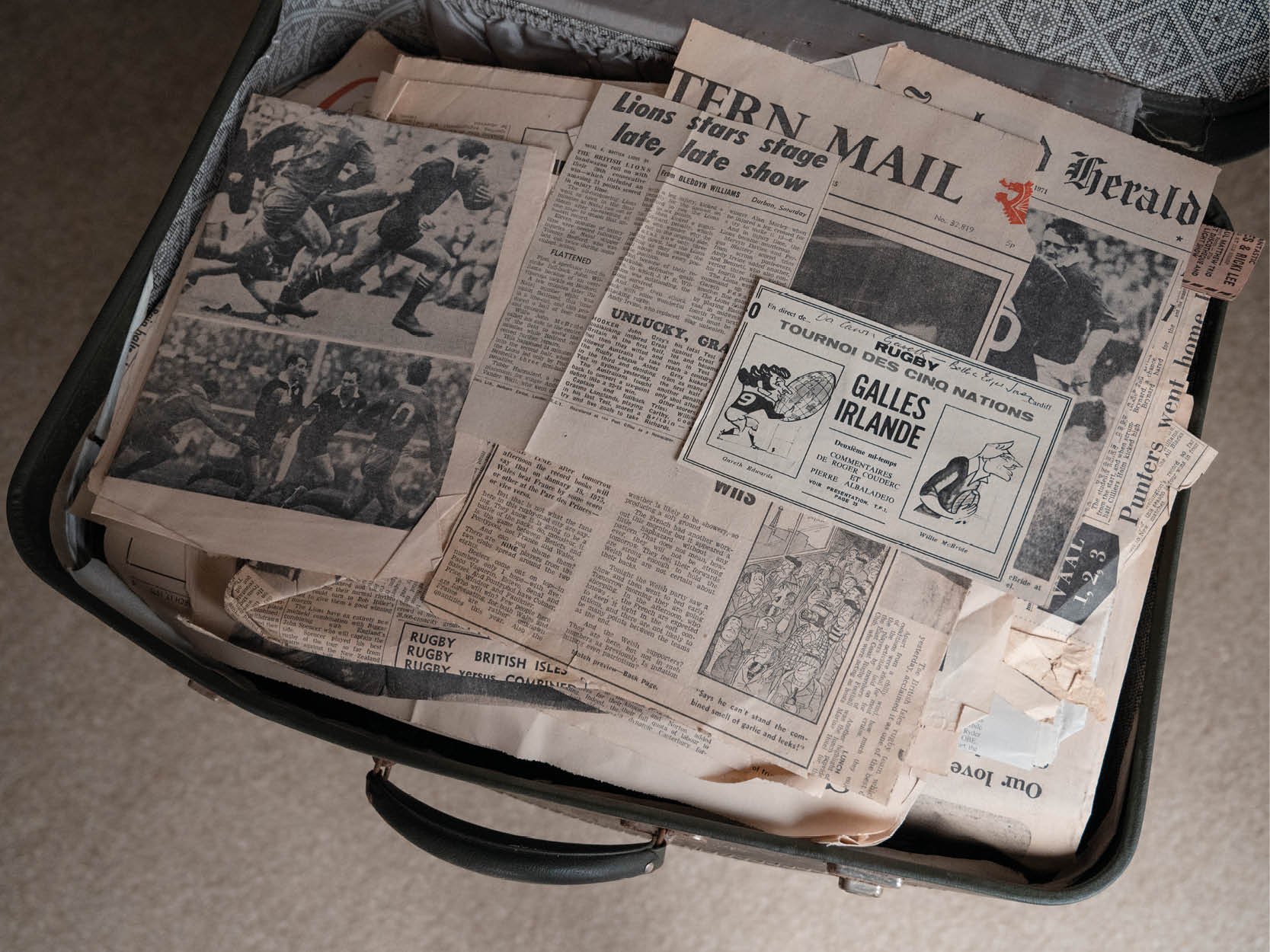

Sir Gareth’s house is everything a rugby fan could want it to be. A snooker room doubles as a museum of the greatest moments in Welsh, British & Irish and Barbarian rugby, it just so happens that this one man was there for them, and indeed inspired, created or sealed many of them. The ‘archive’ he’d mentioned, appears to be an old suitcase full of newspaper cuttings from New Zealand and Wales.

While Maureen apologises for the cold – “it’ll warm up in a bit, now I’ve put the heating on,” she says – Gareth walks around picking up a few of his favourite bits and pieces: an original signed leather match ball from the third South African Test in 1964; a shelf of bespoke Groggs, including one by the founder and a quartet of statues, one for each of his ‘sides’ – Cardiff, Lions, Wales and Barbrarians; and then you get to the fishing and golf paraphernalia, a 30lb pike hangs on the wall beneath a picture of Gareth wrestling with the 40lb-er he caught for a British record. There’s a signed Ryder Cup picture above a clutter of assorted golf clubs, although Maureen must take credit for the presence of some of these, and then out in the garden they have a ‘halfway house’ full of their favourite golfing moments, including the time Gareth played with Seve.

Fishing and golf achievements aside, Gareth’s multi-faceted game made him not just one of the greatest rugby players of his era, which itself was arguably the greatest of all eras, but a player whose abilities are still admired by everyone within the game. He won three Grand Slams, seven Five Nations, and scored 69 tries in 195 games for Cardiff, a club for which he later became a director.

“I’ve got a book over there,” he says, pointing to a book shelf creaking with assorted rugby memoirs, “and I co-wrote it with a BBC guy at the time, and it was about Wales’s golden era. And when you look back at those moments, it’s not necessarily scoring ones that stand out. There are tries I’ve scored going from here to there [he highlights a distance of a foot], which have meant as much if not more because they were so important.

“There was one match in Dublin, and I can remember turning to Gerald [Davies] and saying. ‘I don’t like this, it’s too easy for Lansdowne Road’. In our first two or three moves we scored, which at Lansdowne Road was very hard to do, but then came the onslaught, the Irish fervour, and before you know it, you’re battling for air, our line was under threat and we were defending just to stay in the game.

‘I knew if we could just get the ball out we had a chance to score, and Bobby Windsor and Charlie Faulkner were right in at the coalface, and just managed to get it out and then it was out and along the line and we scored. We had to claw our way out of trouble, but then to see the beauty of the last move for JJ to score and win us the game – that will live with me forever. I think it was another Grand Slam at the end of it, but however we got out of that I’ll never know, but that was the ability of the team.”

So, your greatest moment is turnover? “Yup, I can remember that every bit as much as I can running for that try.”

Gareth toured with the Lions three times, first in 1968 to South Africa, just a year after making his Wales debut, aged nineteen, and then the famous tours of 1971 to New Zealand and 1974 to South Africa. “You can’t differentiate between ’71 and ’74,” he says. “71 was possibly the best achievement because nobody had ever done it before, but after we won in New Zealand I remember everyone saying, ‘well done boys you’ve beat the All Blacks, now go and beat the South Africans...’.

“Expectation was great, but I’d been to South Africa with Cardiff and the Lions, so knew the hard pitches, playing at the Highveld, all produced different scenarios to what New Zealand offered. Although, in actual fact, we had a very strong pack in South Africa so it’s not really a comparison, it’s just two great moments.”

Arguably the best achievement of the tours was outside of the Test arena. “When Ben Blair played for Cardiff, I was a director, and he was very quiet and shy, never said much, and he came up to me one day, and said ‘I didn’t realise you were unbeaten in provincial games. For me that was the achievement not the Test matches’. And it made me think about it, maybe he was right. Wednesday/Saturday/Wednesday/Saturday – Canterbury/Wellington...

“Ben said, he could understand how we could win a Test series, it’s four games, you win one, you can nick one, lose one, draw one and you’ve got the series, but you can’t do that in provincial games.”

Gareth turned down the chance to tour New Zealand in 1977, a year before he would retire. He admits to being able to see the Welsh era coming to an end. “Yeah, yeah,” he quickly responds. “There were more and more pressures – even from the time I played and finished – on players’ time as an amateur, that wasn’t sustainable.

“I think the powers that be were so pre-occupied with protecting the game, they were losing sight of what was happening underneath. And of course the game was changing: more television, more pressure, there were lots of guys who worked in the city and holding down jobs because they were good rugby players, so they couldn’t hold on. It was only going to be a matter of time before Kerry Packer – who was behind a rival professional rugby circuit that forced the game to go professional – or someone else came along.”

As with most of his contemporaries in the Welsh squad, Gareth had been approached by the rival code. “You’d be prodded every now and then with a rugby league offer,” he says, “and you had to notify the union if you’d been approached. You could just be passing a bloke in the street, or someone would pull up in a car, and say ‘I’m from Wigan or whatever’, and you had to tell the union. You could be banned for not telling them.”

He’d always resisted, staying loyal to union. “We were amateurs holding down jobs, I was working for an engineering company, for people who were very good friends. I qualified as a teacher but I didn’t really feel that’s what I wanted to do, so I had a bit of an engineering background in the school I’d been to before Millfield, so it was guaranteed work, and they were a fabulous family and people to work for.

“I remember when I first went to work for Jack [his employer],” he recalls. “My parents knew them from school, and he said, ‘come and work for me, I can’t promise I’ll make you a millionaire, but if you want to go on tours...’.

“But there were more and more tours. Training used to be once in a blue moon, then it was every week... And I think it was only one year in the ten or twelve seasons I played that I didn’t go on tour. My company were paying me, and of course they [the union] still made a song and dance about that, but if it had not been for benevolence of my employer I couldn’t have done it. How can you go for three and a half months on a Lions tour and not be paid? The hierarchy would turn a blind eye though, because if they didn’t they wouldn’t have a side would they?”

When the 1977 tour came around, he knew he had to consider whether or not he wanted to ask for the time off again.

“I was playing alright enough, to maybe be considered, so I thought ‘do I want to?’” he says. “I had family, I had kids, then I was thinking ‘Wales are off in 1978 to Australia, then another Lions tour in 1980, so do I really want to do that? Can I ask Maureen again, can I ask my boss – who was a father figure to me – again?’ I spoke to Jack about it, and he said, ‘Gareth, if Maureen can do without you, then I can do without you’.”

“You had two children, two babies,” chips in Maureen, making us another cup of tea. “He could do what he liked for his rugby. You know what happened with the first one?” she asks. We didn’t. “I was still in hospital with our first child, and he went off to South Africa [1974] for three and half months, and I came back home, walked into the house, crying, and my sister said, ‘stop your nonsense will you, he’ll back in three and a half months!’ So I snapped out of it and got on with it.”

With sons Rhys and Owen, then four and three, and Maureen front of mind Gareth didn’t make it to New Zealand in 1977, as he took the first steps towards retiring.

He was bringing to an end a career that undoubtedly made his father proud, even though he’d never been able to play rugby himself. “My father lost his father when he was thirteen, so had to work underground in the mines from that age,” Gareth says. “And my grandfather who’d died had played rugby. And, so I’m led to believe, after one game, he’d put his overcoat on, and go and have a few beers, then go home for a bath. That was what they all did back then, but because of that he got pneumonia and passed away. He was only 25.

“So my father never had the opportunity to play really,” he continues, “but he gave me all the help that he could in taking me to matches, and helped me get into Millfield by selling his prized possession, the caravan.”

“You paid what you could afford,” says Maureen of the need to pay towards the scholarship. “We’d never heard of Millfield in the village before,” she continues. “He said to me, ‘will you write to me?’, I said, ‘where’s Millfield?’.”

Theirs is an enduring love story. “We’ve been married 50 years,” says Gareth, before Maureen tells the full story. “We both failed the eleven plus and ended up at the same school, in the same class, when we were eleven.

“We were both from a village below the Black Mountains, and born on the same street, his birth certificate says number eleven, mine says 55. And I didn’t have to change my name either, I was an Edwards.”

“Don’t read too much into that!” interjects a laughing Gareth.

“I’ve been so fortunate,” he concludes. “There were many obstacles and fences in the way that I had to get over, that could’ve sent me on to so many different pathways, but now at this age I’m lucky I can still fish, play golf, go for walks, I’ve survived to have a physical life after playing a tough game.”

His final game came against France, in 1978. As was the theme of his career, Wales won. “The crowd ran on the field, they’re lifting you up, saying ‘well done boys’, ‘fantastic’, ‘title again’ or whatever again. ‘Now go and beat New Zealand, then Australia, then South Africa’, and it made me realise for a moment, that, in the nicest way, they’ll never be satisfied, there’ll always be another game.

“And at that moment, still on the pitch, covered in mud, being pulled this way and that, in the drama of the end of a match, it sort of came clear to me, that this will never be over! And I don’t mean that to sound negative, but as far as they were concerned, they’re not happy with a Grand Slam they want another of this or that.

“I didn’t retire then though,” he says. “I wasn’t going to finish at the end of a season when you’re tired. It would always be when you smelt the grass in September – that tells you if you want to go on. But it crossed my mind in a flash then, there was always going to be another game, and I think I’d begun to appreciate the children, and my boss who had never said ‘no’, Maureen...”

“And one of the boys had said, ‘don’t go there again dad, they’ll kick your head in’,” adds Maureen. “And, yes,” responds Gareth, “the kids were noticing.”

Then, after he’d made the decision internally, he received a letter from the WRU. “Well of course, I did have a letter from them, saying ‘rumour has it, Fleet Street is rife with news of your retirement and you’ve got a book coming out...’ they were more concerned about the amateur status than anything else. But, once you’d written your book that professionalised you.”

And so ridiculously, but in a fashion typical of the amateur era, despite being retired, he was banned. It mattered little in the grand scheme of things. He had Grand Slams, Five Nations titles, Lions series wins, that try, global respect, his loyal boss, his two boys, and of course his Maureen.

“Yes,” he admits, “she’s been very patient.”

Story by Alex Mead

Illustrations by Mark Long

Pictures by Francesca Jones

This extract was taken from issue 20 of Rugby.

To order the print journal, click here.